CrowdStrike® Intelligence has identified a new ransomware variant identifying itself as BitPaymer. This new variant was behind a series of ransomware campaigns beginning in June 2019, including attacks against the City of Edcouch, Texas and the Chilean Ministry of Agriculture.

We have dubbed this new ransomware DoppelPaymer because it shares most of its code with the BitPaymer ransomware operated by INDRIK SPIDER. However, there are a number of differences between DoppelPaymer and BitPaymer, which may signify that one or more members of INDRIK SPIDER have split from the group and forked the source code of both Dridex and BitPaymer to start their own Big Game Hunting ransomware operation.

INDRIK SPIDER Origins

INDRIK SPIDER was formed in 2014 by former affiliates of the GameOver Zeus criminal network who internally referred to themselves as “The Business Club.” Shortly after the group’s inception, INDRIK SPIDER developed their own custom malware known as Dridex. Early versions of Dridex were primitive, but over the years the malware became increasingly professional and sophisticated. In fact, Dridex operations were significant throughout 2015 and 2016, making it one of the most prevalent eCrime malware families. At this time, INDRIK SPIDER was primarily conducting wire fraud, resulting in the loss of millions of dollars globally.

Over time, INDRIK SPIDER encountered a number of obstacles to their wire fraud operations. First, in 2015 the group had to overcome a takedown operation, which resulted in the arrest of one of its affiliates, who used the alias “Smilex.” This setback was followed by a law enforcement operation in the U.K. designed to break up the money laundering network supporting INDRIK SPIDER’s monetization of Dridex campaigns. The dismantling of this network also coincided with the arrest, and subsequent imprisonment, of a U.K. bank employee who helped set up fake accounts.

Perhaps as a result of these obstacles, INDRIK SPIDER changed their methods of operation in 2017, conducting smaller Dridex distribution campaigns. In August 2017, the group introduced BitPaymer ransomware and began to focus on leveraging access within a victim organization to demand a high ransom payment.

BitPaymer Origins

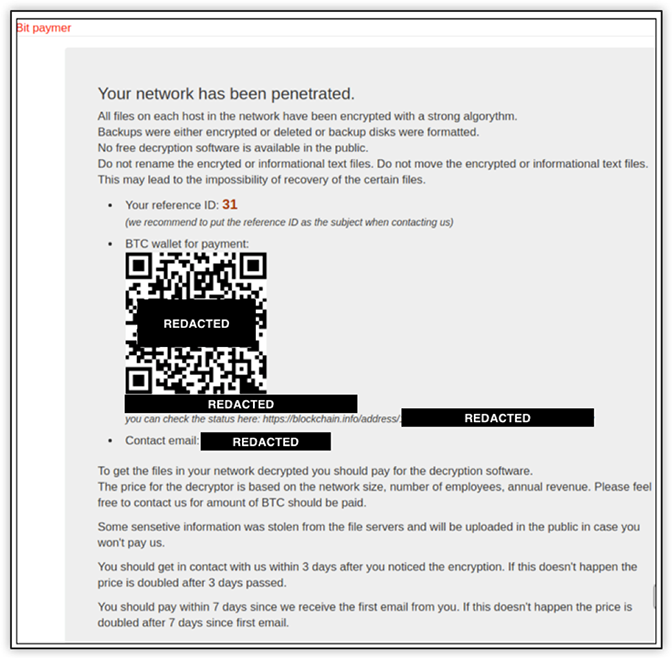

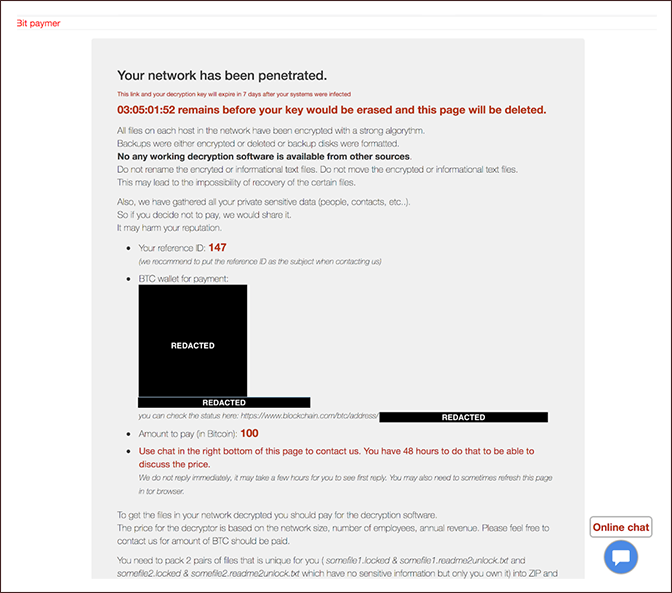

CrowdStrike Intelligence, has tracked the original BitPaymer since it was first identified in August 2017. In its first iteration, the BitPaymer ransom note included the ransom demand and a URL for a TOR-based payment portal. The payment portal included the title “Bit paymer” along with a reference ID, a Bitcoin (BTC) wallet, and a contact email address. An example of this portal is shown in Figure 1.

Within the first month of operation, the ransom amount was dropped from the ransom note. In July 2018, the payment portal URL was also removed. From July 2018 until present, the ransom note has only included two contact emails, which are used to negotiate the ransom.

Figure 1. Original BitPaymer Payment Portal via a TOR Hidden Service

Latest BitPaymer Version

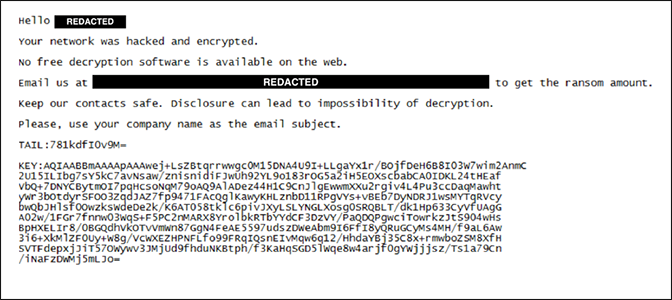

In November 2018, there was a significant update to BitPaymer. The ransom note was updated to include the victim’s name, and the file extension appended to encrypted files was also customized to use a representation of the victim’s name. An example of the new ransom note is shown below in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Latest BitPaymer Ransom Note

In addition to the updated ransom note and encrypted file extension, BitPaymer’s file encryption routine was updated to use 256-bit AES in cipher block chaining (CBC) mode with a randomly generated key and a NULL initialization vector. Previous versions of BitPaymer had used 128-bit RC4.

Since AES is a block cipher, the implementation requires padding in cases where the data is not a multiple of the block size. Typically, this is implemented by adding zeros or the number n of padding bytes n times (also known as PKCS#7). However, INDRIK SPIDER chose to generate n bytes randomly for padding. As a result, the malware developer had to preserve the random padding bytes in order to correctly decrypt the last data block of an encrypted file. This is reflected in the BitPaymer ransom note with a new field of TAIL, as shown above in Figure 2, which contains the Base64-encoded TAIL padding and encrypted AES KEY.

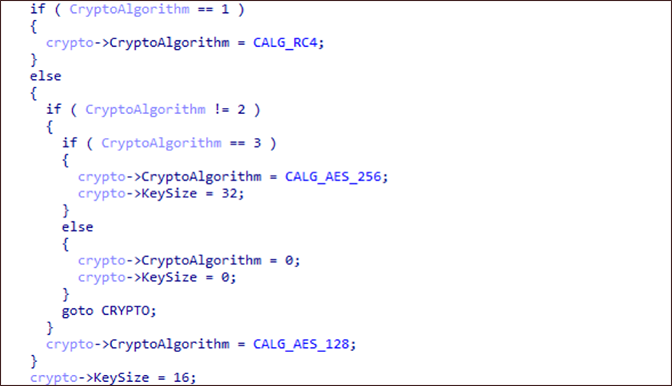

Interestingly, the BitPaymer developers implemented an encryption initialization function in the ransomware code that selects one of three desired encryption algorithms. The algorithm is chosen by an argument that is passed as an integer parameter to the function. The current values supported are 1, 2, and 3 for 128-bit RC4, 128-bit AES and 256-bit AES, respectively. Newer versions of BitPaymer pass the hard-coded value of 3 for 256-bit AES encryption into the function, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Latest BitPaymer Encryption Selection Pseudocode

Along with the updated file encryption routine, the size of the victim-specific RSA public key has also been increased from 1,024-bit to 4,096-bit. This asymmetric key is used to encrypt the generated symmetric file encryption keys. If the ransom is paid, INDRIK SPIDER will provide a decryption tool that contains the corresponding victim’s RSA private key.

It is unclear why INDRIK SPIDER moved from RC4 to AES encryption, but it may be due to concerns about the relative weakness of RC4 in comparison to AES. The increase in the RSA key size also greatly augments the cryptographic strength protecting the file encryption keys. However, there is no evidence that BitPaymer’s prior or current encryption has been broken.

Since the update in November 2018, INDRIK SPIDER has actively used the latest version of BitPaymer in at least 15 confirmed ransomware attacks. These attacks have continued throughout 2019, with multiple incidents occurring in June and July of 2019 alone.

Meet DoppelPaymer

While the first known victims of DoppelPaymer were targeted in June 2019, we were able to recover earlier builds of the malware dating back to April 2019. These earlier builds are missing many of the new features found in later variants, so it is not clear if they were deployed to victims or if they were simply built for testing.

To date, we have identified eight distinct malware builds and three confirmed victims with ransom amounts of 2 BTC, 40 BTC and 100 BTC. Based on the USD to BTC exchange rate at the time of this writing, these ransom amounts vary from approximately $25,000 to over $1,200,000.

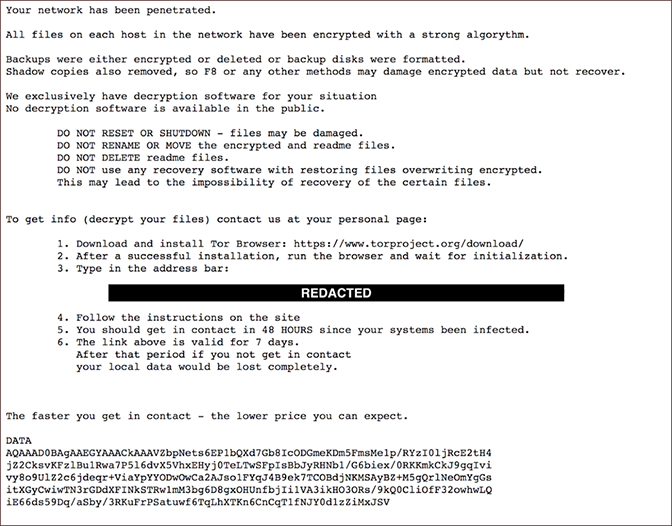

The ransom note used by DoppelPaymer is similar to those used by the original BitPaymer in 2018. The note does not include the ransom amount; however, it does contain a URL for a TOR-based payment portal, and instead of using the keyword KEY to identify the encrypted key, the note uses the keyword DATA as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. DoppelPaymer Ransom Note

The payment portal for DoppelPaymer is almost identical to the original BitPaymer portal. The “Bit paymer” title is still present on the web page and a unique ID is still used to identify the victim. The portal provides a ransom amount, a countdown timer and a BTC address where the ransom payment can be sent. An example of the DoppelPaymer ransom portal web page is shown below in Figure 5.

Figure 5. DoppelPaymer Ransomware Payment Portal

DoppelPaymer and BitPaymer Encryption Comparison

Although DoppelPaymer and BitPaymer share significant amounts of code, there are some notable encryption differences, which are described in Table 1.

| DoppelPaymer | BitPaymer | |

| Ransom note | Each readme file contains an encrypted 256-bit AES key in a field named DATA. |

Each readme file contains an encrypted 256-bit AES key in a field named KEY.Older versions contained an encrypted 128-bit RC4 key in the KEY field. Current versions use anonymous email services such as ProtonMail for ransom payment negotiations. |

| Encryption | 2048-bit RSA + 256-bit AES | 4096-bit RSA + 256-bit AES. Older versions used 1024-bit RSA + 128-bit RC4. |

| Encryption (AES) padding scheme | Standard padding (PKCS#7) | Random bytes specified in a field named TAIL |

| Ransom filename | Encrypted files are renamed with a .lockedextension. |

Encrypted files are renamed with the victim name as the extension. Older versions are appended the suffix .locked to the names of encrypted files. |

Table 1. Encryption-Related Differences Between DoppelPaymer and BitPaymer

There are obvious similarities between the tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) used by DoppelPaymer and prior TTPs of BitPaymer, such as the use of TOR for ransom payment and the .lockedextension. However, the code overlaps suggest that DoppelPaymer is a more recent fork of the latest version of BitPaymer. For example, in the latest version of BitPaymer, the code for RC4 string obfuscation reverses the bytes prior to encryption, and includes a helper function that provides support for multiple forms of symmetric encryption (i.e., RC4, 128-bit AES, and 256-bit AES), as shown in Figure 3.

New DoppelPaymer Features and the Use of ProcessHacker

In addition to the changes discussed above, numerous modifications were made to the BitPaymer source code to improve and enhance DoppelPaymer’s functionality. For instance, file encryption is now threaded, which can increase the rate at which files are encrypted. The network enumeration code was updated to parse the victim system’s Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) table, retrieved with the command arp.exe -a. The resulting IP addresses of other hosts on the local network are combined with domain resolution results via nslookup.exe. (In a similar approach, previous versions of BitPaymer made use of the command net.exe view to enumerate network shares.)

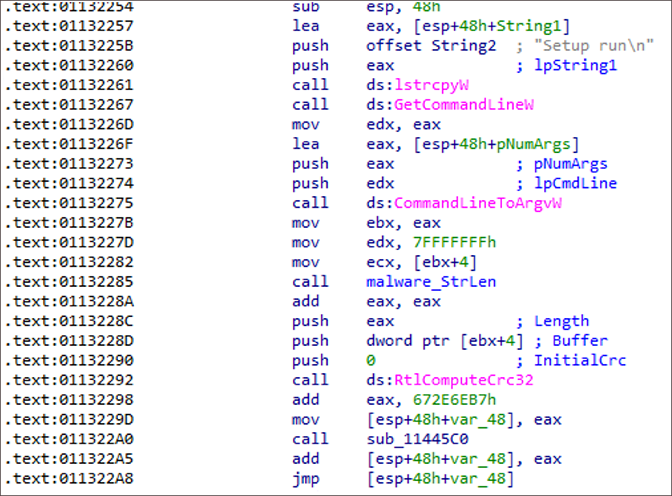

In addition, DoppelPaymer is designed to run only after a specific command line argument is provided. The malware computes a CRC32 checksum of the first argument passed on the command line and adds it with a constant value that is hard-coded in the binary. The malware then adds the instruction pointer address to this result, which becomes the destination for a jmp used to continue the malware execution. The hard-coded constant value is unique to each build. In the sampled analyzed, this value was 0x672e6eb7, as shown below in Figure 6.

Figure 6. DoppelPaymer Control Flow Obfuscation

If no arguments are provided, or if an incorrect value is provided on the command line, DoppelPaymer will crash. This design was likely intended to hinder automated malware analysis environments.

Perhaps the most interesting change that the DoppelPaymer author made is to terminate processes and services that may interfere with file encryption. DoppelPaymer contains several lists of CRC32 checksums of process and service names that are blacklisted. The malware author included CRC32 checksums rather than strings to hinder reverse engineering efforts. However, it is possible to brute-force all of the checksums and recover the respective strings, as shown in Tables 7-11 found in the Appendix.

ProcessHacker

In order to terminate some of these processes and services, DopplePaymer uses an interesting technique that leverages ProcessHacker, a legitimate open-source administrative utility. This application is bundled with a kernel driver that can be used to terminate processes and services. DoppelPaymer is bundled with six portable executable (PE) files that are encrypted and compressed in the malware’s sdata section. These PE files contain 32-bit and 64-bit versions of the following:

- ProcessHacker application

- ProcessHacker kernel driver

- A custom stager DLL that is used to exploit ProcessHacker

The modules are extracted by using the first 16 bytes of the sdata section as an RC4 key to decrypt the next 4 bytes of data, which is the size (big endian) of the subsequent encrypted data. The encrypted data that follows also uses the first 16 bytes as an RC4 key to decrypt the remaining data. The format is shown below in Table 2.

| 16 Bytes | 4 Bytes | 16 Bytes | M Bytes |

| RC4 key | Encrypted data size (M) | RC4 key | Encrypted data |

Table 2. Format of Encrypted DoppelPaymer ProcessHacker Related Modules

After decryption, the first 4 bytes are the size of the compressed data, and the next 4 bytes are the size of the uncompressed data, followed by the compressed data as shown in Table 3.

| 4 Bytes | 4 Bytes | N Bytes |

| Compressed size (N bytes) | Uncompressed size | Compressed 32-bit and 64-bit Process Hacker modules |

Table 3. Format of Encrypted DoppelPaymer ProcessHacker Related Modules Header and Data

The data is decompressed using aPLib, which produces the PE files in a custom structured format, where each PE contains an 8-byte header consisting of a magic 4-byte value, followed by another 4-byte value that specifies the size of the following PE data as shown in Table 4.

| 4 Bytes | 4 Bytes | N Bytes | 4 Bytes | 4 Bytes | N Bytes | |

| Magic value 1 | Size of Module 1 | Module 1 | Magic value 2 | Size of Module 2 | Module 2 | … |

Table 4. DoppelPaymer ProcessHacker Packed Module Format

Table 5 contains the magic value and SHA256 hash for each ProcessHacker component.

| Magic Value | SHA256 | Description |

0xf03d9386 |

51d8618ec86159327e883615ad8989c7638172cf801f65ab0367e5b2e6af596a |

DoppelPaymer’s ProcessHacker Stager DLL (32-bit) |

0xa68d9640 |

d4a0fe56316a2c45b9ba9ac1005363309a3edc7acf9e4df64d326a0ff273e80f |

ProcessHacker3 (32-bit) |

0x53e9cd92 |

0f97f6d53fff47914174bc3a05fb016e2c02ed0b43c827e5e5aadba2d244aecc |

KProcessHacker3 Kernel Driver (32-bit) |

0x2fb0f795 |

bfb7e62ba4ad5975e68a1beefb045cb72e056911fd7a8b070a15029dfcbbefe1 |

DoppelPaymer’s ProcessHacker Stager DLL (64-bit) |

0x7900f253 |

bd2c2cf0631d881ed382817afcce2b093f4e412ffb170a719e2762f250abfea4 |

ProcessHacker3 (64-bit) |

0x8c64a981 |

70211a3f90376bbc61f49c22a63075d1d4ddd53f0aefa976216c46e6ba39a9f4 |

KProcessHacker3 Kernel Driver (64-bit) |

Table 5. Encrypted PE Files Embedded in DoppelPaymer

After decompression, all three binaries are written to the same directory. Both ProcessHacker and the kernel driver are written as random filenames, but the stager DLL filename is chosen to be one of the DLL names imported by ProcessHacker. DoppelPaymer then executes ProcessHacker which loads the stager DLL via DLL search order hijacking. Once loaded, ProcessHacker’s kernel driver is leveraged to kill the blacklisted processes.

DoppelPaymer Links to “Dridex 2.0”

A Dridex loader sample, identified by SHA256 hash 813d8020f32fefe01b66bea0ce63834adef2e725801b4b761f5ea90ac4facd3a, was distributed through the Emotet malware on June 4, 2019. The Dridex sample contained code to decrypt either a 32-bit or a 64-bit core bot module from its sdata section using the exact same encryption, compression, and data format (previously described) that DoppelPaymer uses to extract PEs from its sdata section. This observation ties this Dridex variant directly with DoppelPaymer. The Dridex sample was also unusual; not only because the Dridex loader was bundled with the bot core module (rather than dynamically retrieving it from a C2 server), but also because the bot core module had a version number of 2.0.0.78. We have seen subsequent updates to this new variant of the Dridex bot core module with the latest version being 2.0.0.80 at the time of writing. Of note, prior samples of Dridex had a version number of 4.0.0.87. It’s unclear why the malware author decided to use lower version numbers, but one explanation is that the threat actor views this new creation as “Dridex 2.0.”

Conclusion

Both BitPaymer and DoppelPaymer continue to be operated in parallel and new victims of both ransomware families have been identified in June and July 2019. The parallel operations, coupled with the significant code overlap between BitPaymer and DoppelPaymer, indicate not only a fork of the BitPaymer code base, but an entirely separate operation. This may suggest that the threat actor who is operating DoppelPaymer has splintered from INDRIK SPIDER and is now using the forked code to run their own Big Game Hunting ransomware operations.

To read the original article: https://www.crowdstrike.com/blog/doppelpaymer-ransomware-and-dridex-2/