A novel hybrid data theft-ransomware threat disables security protections by rebooting Windows machines mid-attack.

The Sophos Managed Threat Response (MTR) team and SophosLabs researchers have been investigating an ongoing series of ransomware attacks in which the ransomware executable forces the Windows machine to reboot into Safe Mode before beginning the encryption process. The attackers may be using this technique to circumvent endpoint protection, which often won’t run in Safe Mode.

In mid-October, the Sophos MTR team worked with a targeted organization to investigate and remediate a ransomware outbreak within their network. The ransomware, which calls itself Snatch, sets itself up as a service that will run during a Safe Mode boot. It the quickly reboots the computer into Safe Mode, and in the rarefied Safe Mode environment, where most software (including security software) doesn’t run, Snatch encrypts the victims’ hard drives.

Sophos analysts first encountered the Snatch ransomware about a year ago. The threat actor identities behind the ransomware appear to have been active since the summer of 2018. SophosLabs believes that the Safe Mode enhancement to this malware is a newly added feature.

SophosLabs feels that the severity of the risk posed by ransomware which runs in Safe Mode cannot be overstated, and that we needed to publish this information as a warning to the rest of the security industry, as well as to end users. As we continue to investigate new incidents, we will update this post, and may post a followup in the next few days.

What we refer to as Snatch malware comprises a collection of tooling, which include a ransomware component and a separate data stealer, both apparently built by the criminals who operate the malware; a Cobalt Strike reverse-shell; and several publicly-available tools that aren’t inherently malicious, but used more conventionally by penetration testers, system administrators, or technicians.

One of a growing number of malware families we’ve encountered that have been programmed in Go, Snatch does not appear to be multiplatform. Created by Google, Go was designed to be able to produce programs that, in theory, could run under multiple operating systems.

However, the malware we’ve observed isn’t capable of running on platforms other than Windows. Snatch can run on most common versions of Windows, from 7 through 10, in 32- and 64-bit versions. The samples we’ve seen are also packed with the open source packer UPX to obfuscate their contents.

Snatch’s threat actors job postings

The threat actors behind this malware (who refer to themselves on criminal message boards as “Snatch Team”) appear to have adopted the active automated attack model, in which they seek to penetrate enterprise networks via automated brute-force attacks against vulnerable, exposed services, and then leverage that foothold to spread internally within the targeted organization’s network through human-directed action.

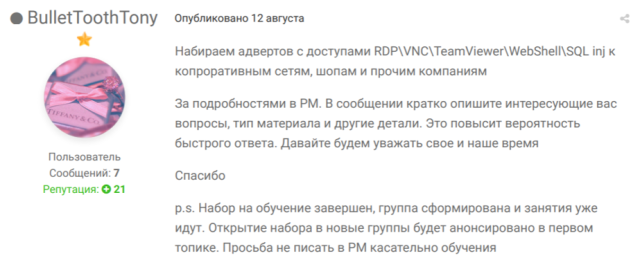

Online posts from criminal boards by suspected members of Snatch Team appear to support the assertion that this is the attacker’s modus operandi. A user (who goes by the online moniker BulletToothTony) soliciting assistance in this type of attack method, writing in a (translated from the original Russian language) message board posting titled “Snatch ransomware” that he is “Looking for affiliate partners with access to RDP\VNC\TeamViewer\WebShell\SQL inj [SQL injection] in corporate networks, stores and other companies.”

Later in the same message thread, this user offers to (at no charge) train others in the use of the malware, allow prospective criminal partners to use their infrastructure, provide “the best students” with a customized server running Metasploit, and then says “we are looking for capable people to join our team.”

Later in the same message thread, this user offers to (at no charge) train others in the use of the malware, allow prospective criminal partners to use their infrastructure, provide “the best students” with a customized server running Metasploit, and then says “we are looking for capable people to join our team.”

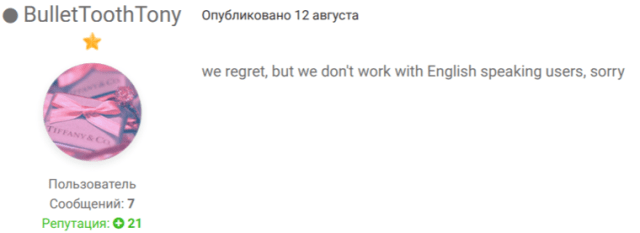

Russian speakers only, apparently. Спасибо, ты такой заботливый.

Russian speakers only, apparently. Спасибо, ты такой заботливый.

The threat actors have also innovated their crime in another important way: One piece of malware used in the Snatch attacks is capable of, and has been, stealing vast amounts of information from the target organizations.

The threat actors have also innovated their crime in another important way: One piece of malware used in the Snatch attacks is capable of, and has been, stealing vast amounts of information from the target organizations.

Deciphering the Snatch attack

In one of the incidents, which targeted a large international company, the MTR team managed to obtain detailed logs from the targeted company that the ransomware had not been able to encrypt. The attackers initially accessed the company’s internal network by brute-forcing the password to an administrator’s account on a Microsoft Azure server, and were able to log in to the server using Remote Desktop (RDP).

Using the Azure server as a foothold, the attackers leveraged that administrator’s account to log into a domain controller (DC) machine on the same network, and then performed surveillance tasks on the target’s network over the course of several weeks.

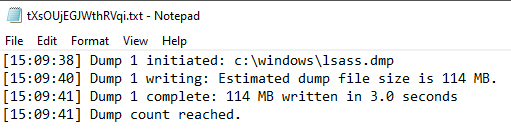

The attackers query the list of users authorized to log in on the box, and write the results to a file. We also observed them dump WMIC system & user data, process lists, and even the memory contents of the Windows LSASS service, to a file…

…then upload them to their C2 server.

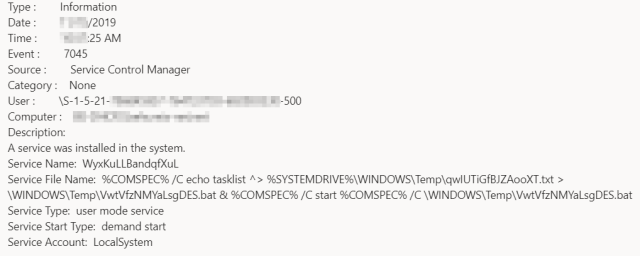

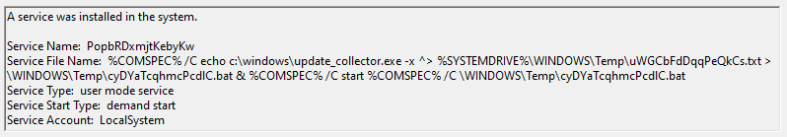

We’ve also observed that the attackers set up one-off Windows services to orchestrate specific tasks. These services have long randomized filenames, such as this one, which queries the list of running processes from the tasklist program, outputs it to a file in the temp directory, then runs a batch file (also located in the temp directory) that uploads the tasklist file to the C2 server.

In fact, it uses this same method to upload a lot of information to the C2 server. For instance, it uses this command to send the extracted user account and other profile information (the .txt file) back to the C2, and then executes a batch file it has created in the Windows temp directory.

In fact, it uses this same method to upload a lot of information to the C2 server. For instance, it uses this command to send the extracted user account and other profile information (the .txt file) back to the C2, and then executes a batch file it has created in the Windows temp directory.

The attackers installed surveillance software on about 200 machines, or roughly 5% of the computers on this particular organization’s internal network. The attackers installed several malware executables; The first group of files appears to be designed to give the attackers remote access to the machines without having to rely on the compromised Azure server.

The attackers installed surveillance software on about 200 machines, or roughly 5% of the computers on this particular organization’s internal network. The attackers installed several malware executables; The first group of files appears to be designed to give the attackers remote access to the machines without having to rely on the compromised Azure server.

The attackers also installed a free Windows utility called Advanced Port Scanner and used that tool to discover additional machines on the network they could target. Following this incident response, we were contacted by another company targeted by this same malware, and the investigation found a copy of Advanced Port Scanner on machines in that network, too.

Sophos analysts also found a tool we suspect was also created by the malware authors named Update_Collector.exe; The tool takes the data that had been collected using WMI to learn more about other machines and user accounts on the network, dumps that information to a file, and then uploads it to the attackers’ command-and-control server. We came across copies on some of the compromised machines.

We also found a range of otherwise legitimate tools that have been adopted by criminals installed on machines within the target’s network, including Process Hacker, IObit Uninstaller, PowerTool, and PsExec. The attackers typically use them to try to disable AV products.

Subsequent hunts for related files revealed several other attacks in which precisely the same collection of tools was used in what appear to be opportunistic attacks against organizations located around the world, including the United States, Canada, and several European countries. All the organizations where these same files were found also were later discovered to have one or more computers with RDP exposed to the internet. Many of the components were found in the Downloads folder for an admin account on the infected system.

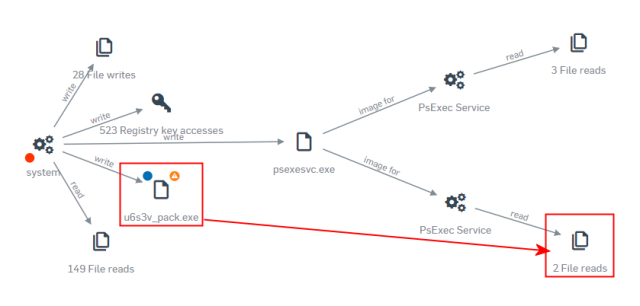

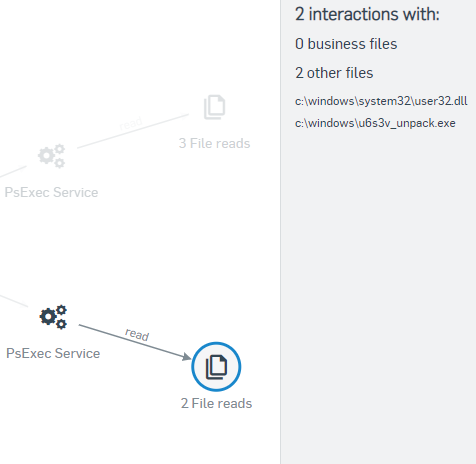

At some point during the attack, which may be several days to weeks after the initial network breach, the attacker downloads the ransomware component to the targeted machine(s). This component arrives on the system with a filename that includes the unique-to-each-victim five-character code and the word “_pack.exe” in the filename.

By the time the malware invokes the PSEXEC service to execute the ransomware, it has extracted itself into the Windows folder with the same five-character code followed by _unpack.exe.

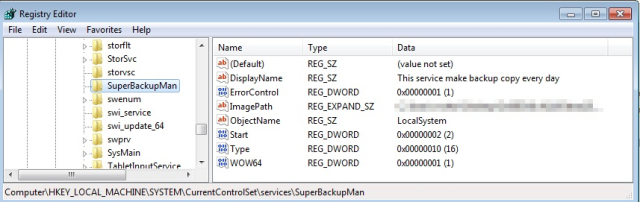

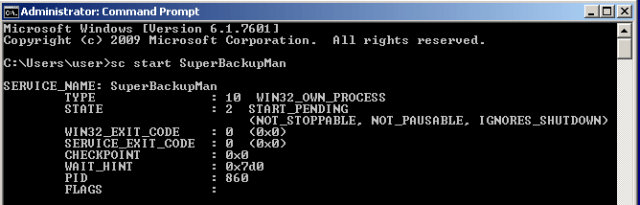

The ransomware installs itself as a Windows service called SuperBackupMan. The service description text, “This service make backup copy every day,” might help camouflage this entry in the Services list, but there’s no time to look. This registry key is set immediately before the machine starts rebooting itself.

The SuperBackupMan service has properties that prevent it from being stopped or paused by the user while it’s running.

The SuperBackupMan service has properties that prevent it from being stopped or paused by the user while it’s running.

The malware then adds this key to the Windows registry so it will start up during a Safe Mode boot.

The malware then adds this key to the Windows registry so it will start up during a Safe Mode boot.

HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\SafeBoot\Minimal\SuperBackupMan:Default:Service

Using the BCDEDIT tool on Windows, it issues a command that sets up windows operating system to boot in Safe Mode, and then immediately forces a reboot of the infected computer.

Using the BCDEDIT tool on Windows, it issues a command that sets up windows operating system to boot in Safe Mode, and then immediately forces a reboot of the infected computer.

bcdedit.exe /set {current} safeboot minimal

shutdown /r /f /t 00

When the computer comes back up after the reboot, this time in Safe Mode, the malware uses the Windows component net.exe to halt the SuperBackupMan service, and then uses the Windows component vssadmin.exe to delete all the Volume Shadow Copies on the system, which prevents forensic recovery of the files encrypted by the ransomware.

net stop SuperBackupMan vssadmin delete shadows /all /quiet

The ransomware then begins encrypting documents on the infected machine’s local hard drive.

The impact of Snatch

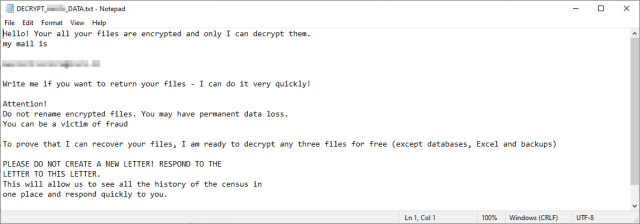

The ransomware appends a pseudorandom string of five alphanumeric characters to the encrypted files. This string appears both in the filename of (and hardcoded into) the ransomware executable, and in the ransom note, and appears to be unique to each targeted organization. For example, if the ransomware is named abcdex64.exe, the encrypted files would have the file extension .abcde appended to the original filename, and the ransom note uses a naming paradigm like README_ABCDE_FILES.txt or DECRYPT_ABCDE_DATA.txt

The attackers were foiled in their attempts to infect machines protected by Sophos endpoint products with the ransomware payloads, or to kill the Sophos endpoint protection services and processes on machines that were attacked. But others were not so lucky. We reached out to Coveware, a company that specializes in extortion negotiations between ransomware victims and attackers. The company tells us they have negotiated with the Snatch criminals on 12 occasions between July and October on behalf of their clients. Ransom demands (in Bitcoin) ranged in value from $2,000 to $35,000, but trended up over that four month period.

The attackers were foiled in their attempts to infect machines protected by Sophos endpoint products with the ransomware payloads, or to kill the Sophos endpoint protection services and processes on machines that were attacked. But others were not so lucky. We reached out to Coveware, a company that specializes in extortion negotiations between ransomware victims and attackers. The company tells us they have negotiated with the Snatch criminals on 12 occasions between July and October on behalf of their clients. Ransom demands (in Bitcoin) ranged in value from $2,000 to $35,000, but trended up over that four month period.

To read the original article: