By limiting physical interactions, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly accelerated the digitization of the banking industry to fulfill customer needs. To cope with the demand, improve access and awareness of financial services, banks and governments are developing new infrastructure, protocols and tools. One of the most successful examples of such initiatives launched during COVID is Pix, the instant payments solution created by the Central Bank of Brazil. Released only in November 2020, Pix has already reached 40 million transactions a day, moving a total of $4.7 billion a week.

Of course, with evolving technology comes evolving hackers. A significant increase in consumers’ use of mobile apps and websites for their banking transactions naturally did not escape the notice of malicious actors, especially those targeting mobile banking.

Check Point Research recently discovered a new wave of malicious Android applications targeting the Pix payment system and Brazilian bank applications. These malicious apps, once distributed on Google Store, seem to be an evolution of an unclassified family of Brazilian bankers analyzed by security researchers back in April, and were discovered to have been updated with new techniques and capabilities. One of the versions we found contains never-before-seen functionality to steal victims’ money using Pix transactions. Due to its unique functionality and implementation, we named this version PixStealer.

PixStealer is a very minimalistic malware that doesn’t perform any “classic” banker actions like stealing credentials from targeted bank applications and communicating with a C&C. Its “big brother” MalRhino, by contrast, contains a variety of advanced features and introduces the use of open-source Rhino JavaScript Engine to process Accessibility events.

In this article, we provide the technical analysis of these malware variants and discuss the innovative techniques they use to avoid detection, maximize the threat actor’s gain, and abuse very specific digital banking features such as the Pix system.

PixStealer: a technical analysis

The PixStealer malware’s internal name is “Pag Cashback 1.4″. It was distributed on Google Play as a fake PagBank Cashback service and targeted only the Brazilian PagBank.

The package name com.pagcashback.beta indicates the application might be in the beta stage.

PixStealer uses a “less is more” technique: as a very small app with minimum permissions and no connection to a C&C, it has only one function: transfer all of the victim’s funds to an actor-controlled account.

With this approach, the malware cannot update itself by communicating with a C&C, or steal and upload any information about the victims, but achieves the very important goal: to stay undetectable.

Figure 1: Virus Total detections of the PixStealer sample.

Like many of the banking Trojans that appeared in the last few years (Evenbot, Gustaff, Medusa, and others), PixStealer abuses Android’s Accessibility Service. AAS’s main purpose is to assist users with disabilities to use Android devices and apps. However, when a victim is lured by banking malware into enabling this service, the Accessibility Service turns into a weapon, granting the application ability to read anything a regular user can access and perform any action a user can do on an Android device.

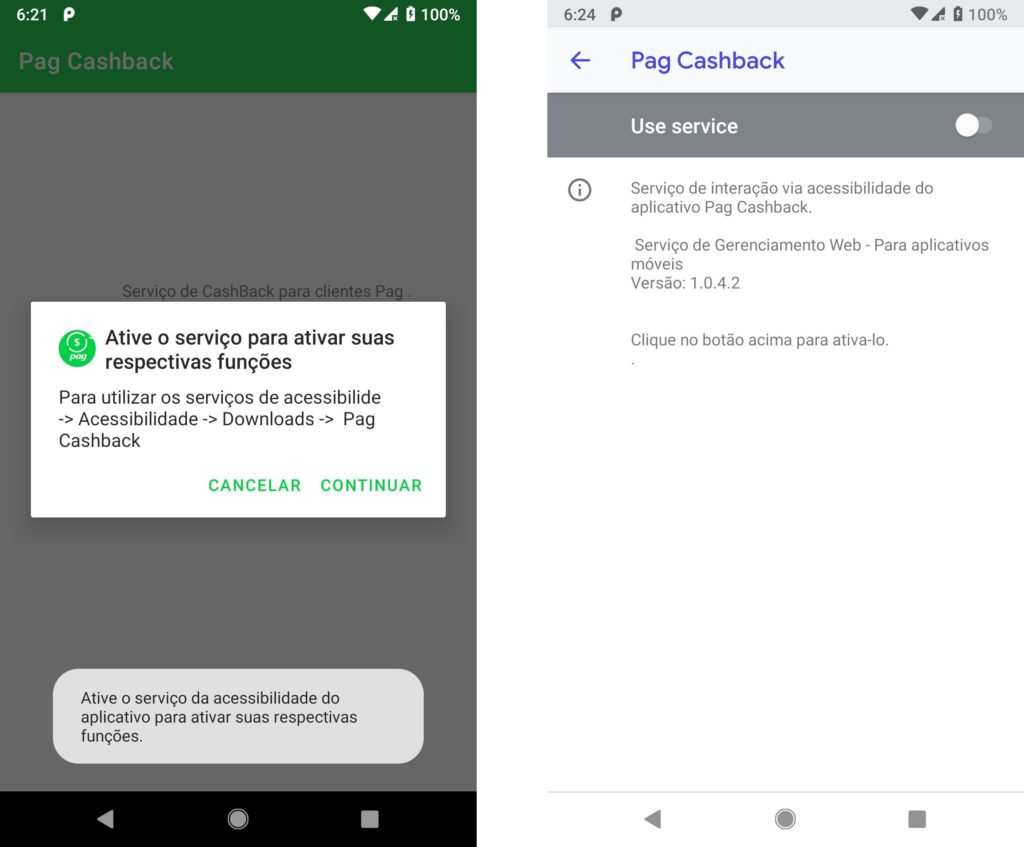

When the application starts, the malware shows the victim a message box asking to activate the Accessibility Service to get the alleged “cashback” functionality:

Figure 2: The PixStealer malware asking for access to the Android Accessibility Service.

Similar to the previous versions of the malware, the service is named com.gservice.autobot.Acessibilidade.

After receiving the Accessibility Service permission, the malware shows a text message with a call to open the PagBank application for synchronization. We should mention that once it has the Accessibility Service access, the malware can open the app by itself. Most likely, it waits for the user to open the app to avoid displaying typical “malware behavior”, which helps it remain undetected.

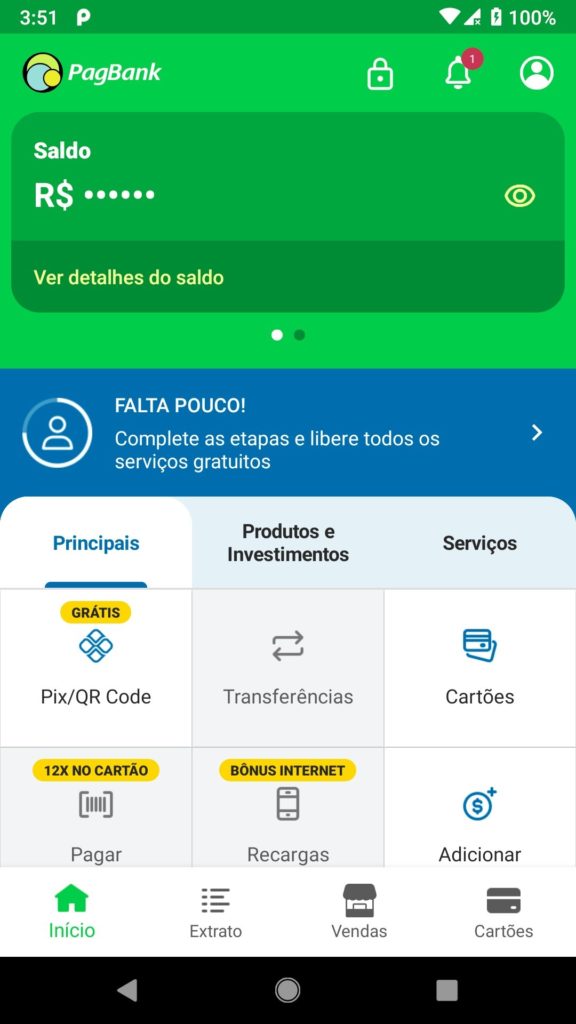

After the victim opens the bank account and enters credentials, the malware uses the Accessibility to click the “show” button to retrieve the victim’s current balance.

Figure 3: The malware will click on the “eye” icon to retrieve the account balance.

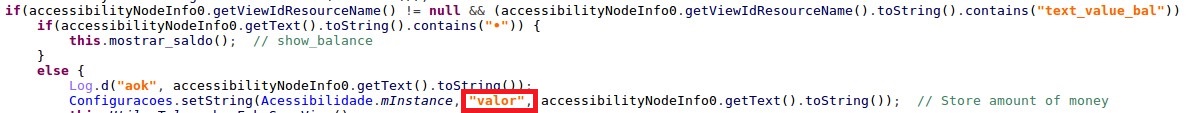

This number is saved to SharedPrefences under the key “valor” (“value” in Portuguese):

Figure 4: The malware saving the account balance to SharedPreferences under key “valor”

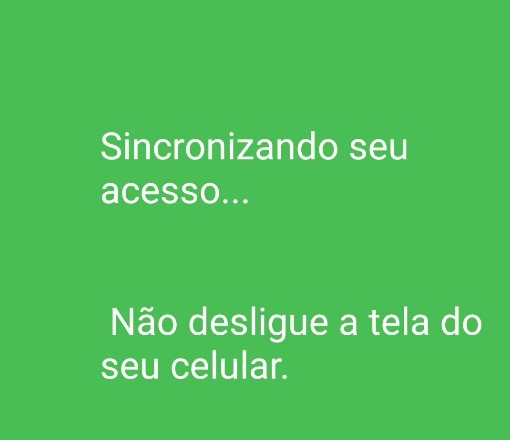

Next, the malware shows a fake overlay view asking the user to wait for the synchronization to finish:

Figure 5: “Synchronizing your access… Do not turn off your mobile screen” overlay screen.

This overlay screen plays a very important role: it hides the fact that in the background the malware is transferring all the funds to the actor-controlled account.

To perform the transfer, the malware first searches for the Transfer button:

Figure 6 : The malware searches for the Transfer button.

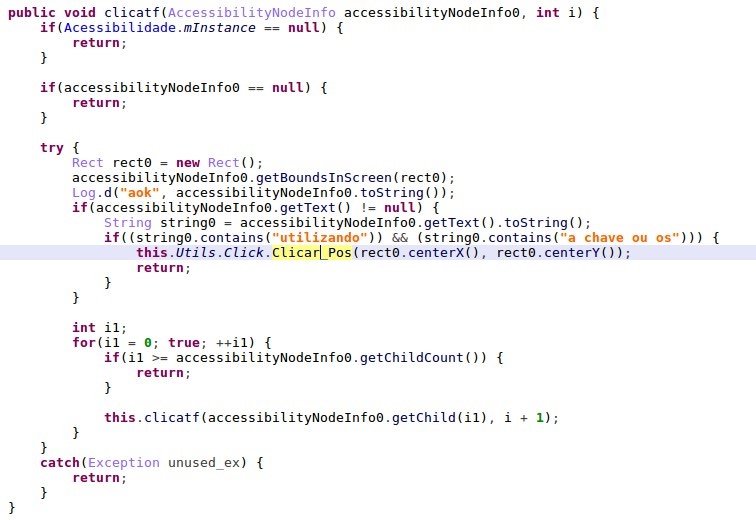

The malware clicks on it by using the following Accessibility actions:

Figure 7: The malware “click on button” function.

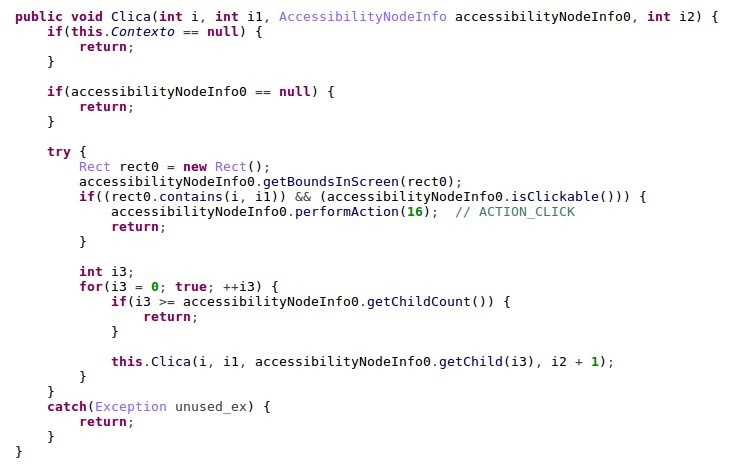

The transfer amount is the value that was retrieved at the start of the app – the entire balance stored in the “valor” key in SharedPreferences:

Figure 8: The malware searches for the text with the string “Informe o valor da transf” (“provide transaction value”) and enters the entire balance value to the transfer amount field.

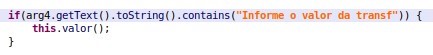

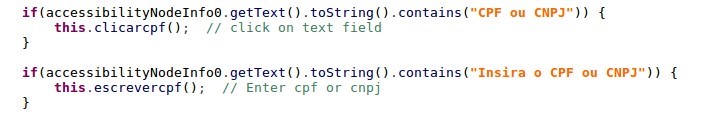

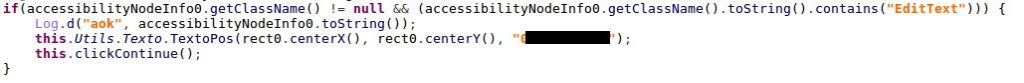

The last action left is to enter the payment beneficiary. The malware searches for the CPF/CNPJ (Brazilian taxpayer identification number) field:

Figure 9: The malware searches for the Brazilian ID field

and then enters the threat actor’s “CPF” (Brazilian ID number) via accessibility functionality.

Figure 10: The malware enters the actor-controlled ID for transfer using Pix.[…]

To read the original article: