Business email compromise (BEC) remains the most common and most costly threat facing our customers. The year 2020 marked the fifth year in which these schemes held the top position on the annual FBI Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) report. Over half a decade, global losses ballooned from $360 million in 2016 to a staggering $1.8 billion in 2020. Put in perspective, the annual losses associated with BEC schemes now exceed the gross domestic product (GDP) of 24 countries. Of greater concern, the combined losses in the three year period 2018-2020 are now estimated to be in excess of $4.93 billion worldwide. This threat shows no sign of slowing down, as losses increased 29% last year to an average of $96,372 per victim.

Over the past half decade, Palo Alto Networks Unit 42 has actively monitored the evolution of this threat with a unique focus on threat actors based in Nigeria, which we track under the name “SilverTerrier.” While BEC is a global threat, our focus on Nigerian actors provides insights into one of the largest subcultures of this malign activity, given the country’s consistent ranking as one of the top hotspots for cybercrime. We have compiled one of the most comprehensive data sets across the cybersecurity industry, with over 170,700 samples of malware from over 2.26 million phishing attacks, linked to roughly 540 distinct clusters of BEC activity.

Since 2016, we have witnessed several high profile arrests of BEC actors, including two arrests of actors accused of stealing $24 million and $60 million respectively. Simultaneously, Nigeria has demonstrated significant growth and outcomes in terms of driving reductions in how brazenly these actors operate. Leveraging our data set, we continue to actively partner with and support industry, government and international law enforcement efforts to combat this threat.

This blog provides a brief history of BEC, examines the evolution of SilverTerrier actors over time, identifies recent malware trends, describes efforts taken to date to combat this activity and provides recommendations to help organizations protect against these threats.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected against the types of BEC threats discussed in this blog by products including Cortex XDR and the WildFire, Threat Prevention, AutoFocus and URL Filtering subscription services for the Next-Generation Firewall.

Defining Business Email Compromise

Before describing the evolution of BEC, it is important to establish a baseline definition of the threat. Given its name, many often mistakenly assume BEC encompasses any and all instances of computer intrusions where an email system is compromised. However, this definition could easily apply to almost any computer incident, ranging from supply chain attacks to ransomware, and is therefore far too broad.

Conversely, law enforcement and the cybersecurity industry rely on a much narrower definition. Specifically, BEC is considered a category of threat activity involving sophisticated scams which target legitimate business email accounts through social engineering or computer intrusion activities. Once businesses are compromised, cybercriminals leverage their access to initiate or redirect the transfer of business funds for personal gain. The remainder of this blog applies this narrow definition of threat activity.

Recent History

The term “business email compromise” was first coined in 2013 when the FBI began tracking a nascent financial cyberthreat. At the time, BEC was simply viewed as a new cybercrime technique joining the ranks of other unsophisticated schemes, for example, the notorious “Nigerian Prince” scams. Yet, with the benefit of time, we have come to see that BEC was a cultural and technological evolution for the cybercrime ecosystem. The internet experienced unprecedented growth in a compressed time frame (2009-2013), much of which continues today. However, what is often overlooked is that the most significant growth during that period of time occurred in developing regions of the world. African nations, in particular, grew at the fastest rate with 27% annual growth, and by the end of 2013, an estimated 16% of the African population was online.

Concurrently, we also witnessed a proliferation of commodity information stealers, remote access trojans (RATs) and penetration testing tools. These capabilities were supplemented with the emergence of cyber certification programs and educational resources, both online and in universities, for how to use these types of tools. It thus becomes readily apparent how actors involved in traditional forms of paper-based mail fraud (Nigerian Prince/advanced fee scams), originating from developing nations, would naturally evolve their tactics to the internet using the newly available tools at their disposal. From a criminal standpoint, it was no longer effective or efficient to send thousands of paper letters through the international mail system and wait for a response. By the end of 2013, they could communicate in real time over the internet and simply send victims malicious files, which enabled their desired criminal outcomes.

Unit 42 has been following this evolution for the past six years. In 2014 we released our first report, 419 Evolution, documenting one the first known cases of Nigerians deploying malware for financial gain. In 2016, we performed focused research on the threat and quickly discovered it had grown to over one hundred different actors or groups. After assigning the code name “SilverTerrier” to Nigerian cyber actors, we detailed the tremendous growth of both actors and malware adoption in The Next Evolution of Nigerian Cybercrime.

In 2017, the threat continued to expand to over 300 actors or groups, and we began to track specific malware tool trends in our annual report, The Rise of Nigerian Business Email Compromise. Our 2018 report, “SilverTerrier: 2018 Nigerian Business Email Compromise Update,” documented that the number of actors surpassed 400, as the number of attempted attacks against our customers climbed to an average of 28,227 per month. Additionally, we began to observe a shift away from simple information stealers as more actors started to embrace RATs, which afforded greater capabilities.

By the end of 2019, this shift in tools had progressed to an established trend, as informational stealer usage declined steadily, while RAT adoption grew an impressive 140% year over year. Our annual report in 2019 also highlighted the emergence of the first set of Nigerian tool developers natively developing their own RATs and crypting tools for sale to their peers.

Finally, as we entered 2020 and began to feel the effects from the global COVID-19 pandemic, we documented yet another milestone as threat groups paused their traditional invoice- and package delivery-related phishing campaigns, in favor of pandemic-related themes. In doing so, BEC actors once again demonstrated their ability to adapt to the ever-changing environment in which they operate.

Actors

What started as a small cluster of activity in 2014 has grown significantly in scope and scale over the past seven years. To date, we have identified 540 distinct clusters of activity which we associate with Nigerian actors and groups. Seeking to understand these actors and their behaviors better, in 2016 we worked to identify commonalities among the actors. At the time, we thought that our efforts would confirm existing stereotypes – that these actors were simply young, unorganized script kiddies whose success was based more on luck than skill. Throughout our research we instead found that the actors were:

- Living Comfortably – The actors were predominantly from the cities of Owerri, Lagos, Enugu, Warri and Port Harcourt in the southwest/coastal region of Nigeria. The majority stayed close to friends and family, where they lived quite comfortably based on the favorable exchange rate between foreign currency and the Nigerian naira. Their social media accounts often flaunted their criminal successes with pictures of foreign currency, huge homes and luxury vehicles such as Range Rovers. Additionally, some of the more successful actors traveled abroad to places like the United Kingdom and Malaysia, where they quickly reestablished their criminal operations.

- Educated – Many of the actors had attended technical secondary school and went on to obtain undergraduate degrees from federal or regionally aligned technical university programs.

- Adults – The actors ranged in age from late teenage years to adults in their mid-40s, thus representing a wide range of generations participating in the criminal activity. The older actors were often found to have evolved to BEC activity from other legacy forms of advanced fee scams, while the younger actors graduating with fresh university degrees began their criminal careers by jumping straight into malware campaigns.

- Not Hiding – While a small subset of the actors went to great lengths to conceal their identities, the culture within Nigeria at the time allowed for a permissive environment for these types of illicit activities. As a result, the actors frequently applied little effort toward maintaining anonymity and often combined fake names or aliases with local street addresses, phone numbers and personal email addresses when registering their malicious domains. In doing so, we found that it was often easy to link these users to their social media and networking accounts on platforms such as Facebook, Google+, LinkedIn, Twitter, Skype, Yahoo Messenger and so on.

- Becoming Organized – Early in the evolution of BEC, we saw that small clusters of actors were beginning to communicate, cooperate, and share tools and techniques. Most commonly, this took the form of an experienced actor standing up malware infrastructure for their friends or younger protégés. Alternatively, we saw actors sponsoring other actors for access to hacking forums, but while there were occasionally large groups of actors working together, such cases were believed to be rare.

Unit 42 is revisiting this historical assessment in 2021, and our analysis provides unique insights into how these actors have evolved over time. By and large, the actors are still living comfortably. Those who were most active in 2016 have grown up; they are now married, have children and have launched legitimate business ventures (hotels, clubs, technology companies, etc.) that were potentially funded through their previous criminal exploits. For those who chose to depart Nigeria, we observed relocation to additional countries in the Middle East, such as Turkey and the UAE.

The majority of the actors continue to be well educated, having completed both secondary and university programs. As these actors age, we see a notable decline in criminal activity as actors reach their mid to late 30s. While the exact reason is difficult to pinpoint, we believe that the decline may be due in part to actor maturation, including an interest in reducing risks as they start families, or simply that they have earned enough through their criminal exploits that they wish to pivot to legitimate business ventures. Conversely, it’s also worth noting that we rarely see young children or teenagers involved in this type of malicious activity. New actors entering the space tend to be in their late teens and early 20s. On the younger side, technical skills and education, more than anything, remain a firm barrier to entry for this type of criminal activity.

Half a decade of change in Nigeria, as well as improved global awareness of the BEC threat, have had a positive effect in driving reductions in how brazenly these actors operate. The Nigerian Federal Police (NFP) and Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) have demonstrated significant growth and outcomes in their efforts to combat this threat and routinely post pictures of the actors they arrest on Twitter accounts. Aiding their efforts, organizations like INTERPOL, the FBI and the Australian Federal Police (AFP) have worked to collaborate internationally to enable global prosecution efforts. Concurrently, in the technology space, there have been mixed developments as collaborative platforms like Yahoo Messenger and Google+ were retired, while privacy improvements across social media platforms have impacted attribution efforts. As for the actors themselves, they have faced growing awareness of the risks associated with their criminal activity as the culture in Nigeria has evolved. While social media accounts may still flaunt their wealth, today it is far less common to see the posts openly discussing illegal activities, pictures of foreign currency or other content that may draw unwanted law enforcement attention.

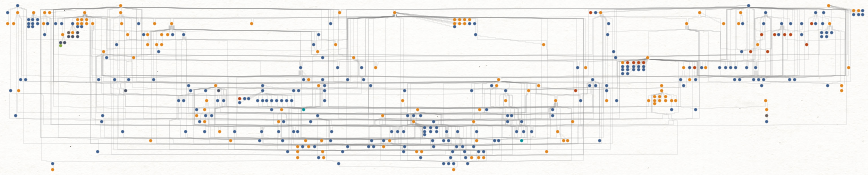

However, BEC actors have become far more organized over time. While it remains easy to find actors working as a group, the practice of using one phone number, email address or alias to register malicious infrastructure in support of multiple actors has made it far more time consuming (but not impossible) for cybersecurity and law enforcement organizations to sort out which actors committed specific crimes. Similarly, we continue to find that SilverTerrier actors, regardless of geographical location, are often connected through only a few degrees of separation on social media platforms. To illustrate that case, Figure 1 shows social media connections between over 120 actors.

Beyond the generalized actor trends identified above, we believe it is helpful to also examine individual actors in order to provide a more comprehensive portrayal of the modern BEC threat actor. Please consider the following examples:

- Example A – Onuegwu Ifeanyi, also known as “SSG Toolz,” was arrested by the NFP in November 2020. Having studied computer science at Imo State University, he launched Ifemonums-Solution LTD as a legitimate business venture in late 2014. That same year, he began his criminal activities, and from 2014 until his arrest, he registered over 150 malicious domains for personal use and to support other actors. Examples include us-military-service[.]com, starwooclhotels[.]com, and gulf-capital[.]net. Many of these domains also served as command and control infrastructure for over 2,200 samples of malware, including Pony, LokiBot, PredatorPain, ISRStealer, ISpySoftware, Remcos and NanoCore. In 2016, he was one of the most active members in the now-defunct “wirewire com” Facebook group, having sponsored 30 other actors to a group focused on performing fraudulent wire transfers. Today his social media portrays a successful businessman, married, with children, driving a Range Rover and traveling the world to places like France, the United Kingdom, Italy and Malta.

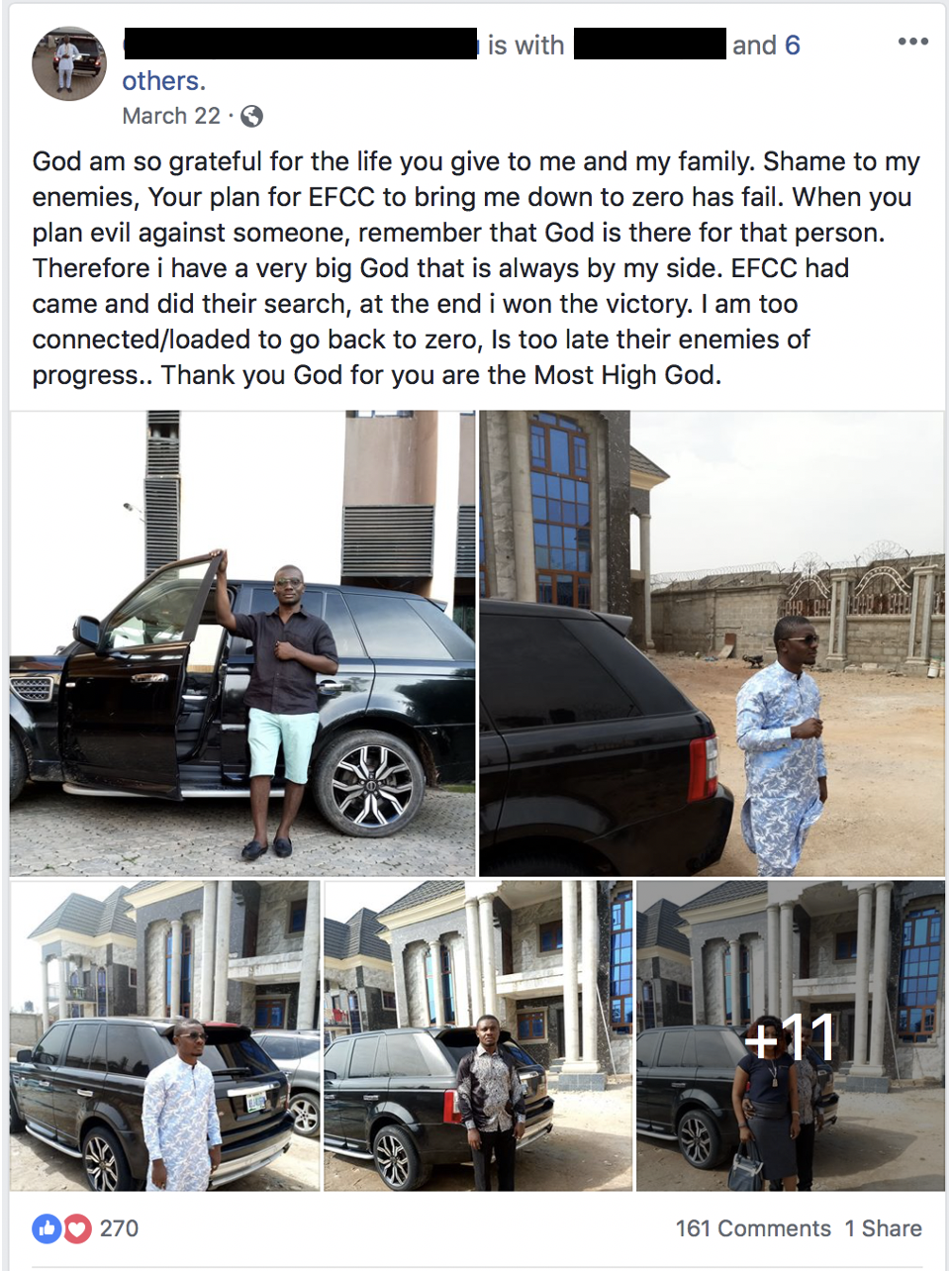

- Example B – This individual also studied at Imo State University. Between 2015 and 2018, he registered 180 domains using a mailing address associated with Jakarta, Indonesia. Several of these domains served as command and control servers for at least 55 samples of malware. Aside from revealing that he also owns a Range Rover, his social media account shows that the EFCC attempted to arrest him in 2018. While the arrest details are unknown, this actor felt compelled to boast about his release afterwards.

- Example C – This actor studied at Lagos State University, is in his 20s and is unmarried. From 2016 to the present, he has registered 55 malicious domains. These domains are linked to over 480 samples of malware. Furthermore, based on the names of the domains, it appears that this actor is likely providing infrastructure to support other actors. Examples include: 247logss[.]info, fergologss[.]us, kinglogss[.]info , and nelsloggs[.]com. Serving as the exception to the rule, this actor is also quite public about his activities on social media. In 2017 he maintained a Facebook account with a background image that said “certified cybercriminal.” Presently, his personal Facebook account contains a background image of the Guy Fawkes/Anonymous mask.

Malware and Business Email Compromise

From 2014 to the present, we have identified over 170,700 samples of malware directly attributed to Nigerian BEC actors. Representatively, this data set serves as the most comprehensive collection of BEC indicators of compromise (IoCs) across the cybersecurity industry. These samples have been observed in over 2.26 million phishing attacks targeting our customers across all industry verticals globally.

Over time, we have taken steps to characterize trends from this data set to empower network defenders. We observed that the period 2014-2017 was marked by steady growth in the adoption of information stealers like Pony, LokiBot, and AgentTesla. This was then followed by a decline in recent years as tool availability declined, and both industry detection rates and the technical skills of actors improved. As such, from 2018-2020, we witnessed a rapid adoption of RATs, with the most popular being NanoCore, Adwind, Remcos, Netwire and a home grown/Nigerian-developed variant of HWorm called WSH RAT.

Yet while we continue to see steady growth and adoption of RATs by SilverTerrier actors, our analysis of telemetry from 2020 through the first half of 2021 found it was also important to consider the influence that the global ecosystem has on their activity. In a pre-COVID world, it made sense to highlight new tools annually, as there were frequent changes in tools marketed to actors on cybercrime forums. While that continued to a certain extent throughout the pandemic, the reality is that we didn’t observe any significant shift among BEC actors toward new tools or capabilities over the past year and a half. Instead, our telemetry shows that these actors generally opted to stick with known tools with demonstrated capabilities and performance. In doing so, they focused their attention on adapting and tailoring their delivery campaigns to the shifting global environment.

If asked to consider the impact of the pandemic from a technology standpoint, many would quickly point out that much of the global workforce shifted to remote work arrangements. Depending on the size and resources of employers, employees began leveraging VPN solutions, employer-provided or personal computing devices, and home internet connections. These developments significantly changed how cybersecurity protections were applied across enterprises, more than any other event in the last decade. Furthermore, this shift may have even influenced employee risk tolerance (e.g. increased suspicion of phishing emails), as their work devices were now connected to their home networks. As a result, BEC actors saw a massive shift in the global attack surface that necessitated a change in their delivery themes and techniques.

In 2019 it was common to see BEC actors build new malware payloads as portable executable files (.exe files) and distribute them using phishing campaigns with business themes such as invoices or delivery notices. At the time, Microsoft Office file formats were also leveraged on occasion, adding a layer of complexity and obfuscation. Two of the most common techniques used in developing these documents included exploit code for CVE-2017-11882 or embedding a malicious macro. In both cases, upon opening, these documents were designed to call out, download and run a malicious payload from an online resource. However, across the totality of the samples we analyzed in 2019, only 3.5% used macros and only 3.6% used the CVE-2017-11882 technique.

As early as January 2020, phishing lures began to change to themes associated with the pandemic. Examples include “Coronavirus in Indonesia: Know how to protect and prevent yourself. Don’t get infected” and “Covid:19 Facial Masks – New Order.” As the themes changed, so too did the target audience and delivery packaging. Portable executables remained popular, but we observed a marked increase in Microsoft Word and Excel documents. By the end of the year, Microsoft Office documents with embedded macros remained steady at 3.5%, but documents utilizing the familiar and well-documented CVE-2017-11882 climbed to 13.5%.

Fortunately, CVE-2017-11882 is now a four-year-old vulnerability, and it makes sense that its effectiveness, and therefore its use, would fade over time. Conversely, macros have a more lasting presence as they are relatively easy to code and rely on unsuspecting victims to enable them. In reviewing our telemetry from the first half of 2021, our preliminary findings show only a minimal number of malware samples using the CVE technique, while 69% of all malware samples are now Office documents with embedded macros.

We know that the global pandemic has driven exponential change in various technologies supporting remote work (cloud computing, video conferencing, etc.). At the same time, we also acknowledge that the astonishing growth curve of malware packaged as Office documents – climbing from a combined 7% in 2019, to 17% in 2020, to 69% in 2021 – warrants further investigation. Taking a deeper look, we found that the raw number of malware samples packaged as Office documents halfway through 2021 already meets or far exceeds the annual number of samples we observed in previous years. As such, we remain confident that there is a definitive growth trend.

At the same time, we believe it is also critically important to understand that between mid-2020 and early 2021, almost every business on the planet revised their cybersecurity posture, changed appliances in their environment, re-architected their network traffic flows, and tightened their network security policies to support remote work practices. The effect of these changes must be considered when analyzing threat trends. Applied in combination and at a macro level, these adjustments significantly altered the visibility of threats across both the perimeter (firewall) and host (endpoint) levels. For example, attachments that may have been permitted following cybersecurity analysis in a corporate work environment may have become blocked by default in a remote work environment. Depending on implementation, such a change would reduce the visibility of threats for a cybersecurity company. Thus, it is nearly impossible to draw an even comparison between pre- and post-pandemic threat activity, as the collection posture across the entirety of the cybersecurity industry has shifted dramatically. We applied this lesson to our observations of malicious Office documents and assessed that our preliminary findings of 69% for 2021 are likely artificially inflated due to changes in collection posture over the past year. However, even after accounting for any artificial inflation, a clear growth pattern remains worthy of recognition by network defenders.

Combating BEC

As a global cybersecurity leader, Palo Alto Networks aggressively pursues its mission to be the cybersecurity partner of choice while protecting our digital way of life. In doing so, our focus extends well beyond the protections that our products and services provide to our customers. We seek to provide thought leadership and threat intelligence broadly across the community, while simultaneously working with law enforcement entities worldwide to thwart future threats.

We are not alone in our vision for stopping malicious cyber activity. Over the past few years, the cybersecurity community has teamed with law enforcement to achieve successful outcomes against this threat on several occasions. As a leader in the industry, we continue to promote such efforts and encourage others across our industry to do the same. One notable example is a joint arrest by Interpol and the EFCC in 2016 of an actor who stole more than $60 million from hundreds of victims, including $15.4 million from just one organization.

Two years later, in 2018, the FBI launched its first global campaign targeting BEC actors, which it called Operation WireWire. Over the course of six months and in close collaboration with Palo Alto Networks, FlashPoint, the National Cyber Forensics Training Alliance (NCFTA) and several others, law enforcement agencies were able to arrest 74 actors worldwide. Building off this trailblazing effort, a year later the FBI launched Operation Rewired, in which another 281 actors were arrested worldwide. This included 167 individuals that were arrested in Nigeria in close coordination with the EFCC.

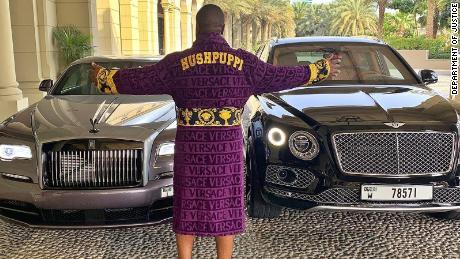

In June 2020, a Nigerian social media influencer who goes by the handle “Hushpuppi” was arrested in Dubai. Though he was known for influencer activities such as posing next to private jets and luxury cars, he was subsequently indicted by the FBI for stealing over $24 million.

Around the same time, we witnessed a significant shift in how U.S. law enforcement entities viewed the challenge of BEC actors operating beyond their reach internationally. While arrests and prosecutions are a vital part of the law enforcement process, it’s also important to acknowledge that BEC is not a problem that we can solve solely through arrests. Other instruments of national power should be applied to this problem set. In June 2020, the United States Attorney’s Office in the District of Nebraska opted to apply U.S. Treasury sanctions to six Nigerian BEC actors for the first time. This action was novel in that it demonstrated an ability to impose a cost on foreign cybercriminals by directly denying access to U.S. financial systems. It further made it illegal for individuals and organizations to transfer funds to these actors and significantly raised the consequences for money mules and others that assisted these actors in their crimes.

As a final example, in November 2020, Interpol, in conjunction with the NFP, arrested three Nigerian actors accused of using 26 different malware families to conduct BEC activities against victims in over 150 countries. Although the total losses are unknown, at the time of the arrest, law enforcement agents discovered a list of 50,000 victims targeted over the course of four years.

Combined, these examples highlight several of the major industry successes in combating BEC activities over the years. Consequently, they also cause us to pause and reflect on the challenges of combating this threat and the financial motives driving its continued existence. In terms of the latter, there is often speculation that because of the technical skills of these actors, it would be devastating if they began adopting ransomware. While such a transition is technically feasible, it is also unlikely for two reasons. First, BEC activities in Nigeria and elsewhere evolved from advanced fee style scams. These scams were generally considered culturally permissible in many places as they were perceived to be akin to jokes, pranks or fooling victims into transferring funds. Conversely, activities demanding ransom payments do not fit this model and tend to be culturally and ethically incongruent with this population of cyber actors. More specifically, it is common to see Nigerian actors speak out in disdain against kidnapping and other ransom-demanding events in their home country. Second, and equally important, it’s difficult to justify a financial motive for BEC actors to switch to ransomware. The examples above show two actors making $60 million and $24 million respectively from their BEC activities. Compare those numbers with the recent Colonial Pipeline ransomware event in which DarkSide demanded $4.4 million and kept almost none of it. It becomes easy to see why pursuing higher-risk, higher-visibility activities like ransomware may not be as appealing or financially profitable as the current BEC status quo.

Finally, as it applies to combating this threat, our experience has shown that the largest challenge is, surprisingly, the ability of law enforcement to identify victims. Given how these schemes work, most victims don’t discover the fraudulent wire transfer until days, weeks or months later. By that time, calling local authorities to investigate is often a moot point, as funds are irrecoverable, and therefore many victims opt not to report the crimes. Conversely, from the vantage point of law enforcement, BEC is a relatively unique form of cybercrime in that the actors perpetrating the crimes are often easily identifiable. Thus, in a reversal of expectations, it is common for investigators to spend considerable time and resources trying to find victims in their specific legal jurisdictions, as the actors themselves and their malware campaigns are already known. Because of this gap, we would conclude by encouraging all organizations who experience a BEC loss to report the event, regardless of timing or circumstances, to organizations like the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3). Doing so will tremendously aid efforts to continue combating this threat in the future.

Protections and Mitigations

The best defense against these evolving threats is a security posture that favors prevention. We recommend that organizations implement preventative practices including:

- Review network security policies, focusing on the types of files (portable executables, documents with macros, etc.) that employees can download and open on devices attached to company networks. Additionally, as a best practice, URL filtering rules should be established to restrict access by default to the following categories of domains: Newly Registered, Insufficient Content, Dynamic DNS, Parked and Malware.

- Routinely review mail server configurations, employee mail settings and connection logs. Focus efforts on identifying employee mail-forwarding rules and identifying foreign or abnormal connections to mail servers. When possible, consider implementing geo-IP blocking. For example, small local businesses do not need to allow logon attempts from foreign countries where they have no employees.

- Conduct employee training. Routine cyberthreat awareness training is one component; however, organizations should also consider tailored training focused on their sales and finance components. Such training should require all wire transfer requests to be validated using verified and established points of contact for suppliers, vendors and partners.

- Conduct tabletop exercises and rehearsal investigations with the intent of determining sources of evidence, as well as gaps in the types of evidence needed, and establishing reporting points of contact for the appropriate authorities. Additionally, rehearsals should validate familiarity with the financial fraud kill chain and make clear that staff know which personnel are responsible for enacting it.

- Conduct compromise assessments on an annual or more frequent basis to test organizational controls and validate that there is no unauthorized activity occurring in the environment. By reviewing mailbox rules and user login patterns on a regular basis, these assessments can verify that controls are functioning as expected and that unwanted behaviors are being effectively blocked throughout the environment.

Finally, for Palo Alto Networks customers, our products and services provide several capabilities designed to thwart BEC attempts, including:

|

Cortex XDR protects endpoints from all malware, exploits and fileless attacks associated with SilverTerrier actors. |

|---|---|

|

WildFire® cloud-based threat analysis service accurately identifies samples associated with information stealers, RATs and Microsoft Office document packaging techniques used by these actors. |

|

Threat Prevention provides protection against the known client and server-side vulnerability exploits, malware and command and control infrastructure used by these actors, including CVE-2017-11882 |

|

Advanced URL Filtering identifies all phishing and malware domains associated with these actors and proactively flags new infrastructure associated with these actors before it is weaponized. |

|

Users of AutoFocus™ contextual threat intelligence service can view malware associated with these attacks using the SilverTerrier tag. |

Conclusion

BEC schemes remain the most profitable and widespread form of cybercrime on the internet today. Last year, global losses from these crimes eclipsed $1.8 billion, and the threat shows no sign of slowing down. Reviewing the recent history of the threat, we have observed positive changes in the ecosystem as the culture in countries like Nigeria has become less tolerant of these activities, and law enforcement entities have stepped up their efforts to find, arrest and prosecute these actors. There is still plenty of work to be done to combat this threat as it shifts toward new delivery techniques in our rapidly evolving world. Commensurate with all of the changes we have seen and implemented in the cybersecurity domain over the past year, we encourage all organizations to invest in a thorough review of controls they have in place to protect against this threat.

To read the original article:

https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/silverterrier-nigerian-business-email-compromise/