Executive Summary

On Sept. 16, 2021, the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) released an alert warning that advanced persistent threat (APT) actors were actively exploiting newly identified vulnerabilities in a self-service password management and single sign-on solution known as ManageEngine ADSelfService Plus. The alert explained that malicious actors were observed deploying a specific webshell and other techniques to maintain persistence in victim environments; however, in the days that followed, we observed a second unrelated campaign carry out successful attacks against the same vulnerability.

As early as Sept. 17 the actor leveraged leased infrastructure in the United States to scan hundreds of vulnerable organizations across the internet. Subsequently, exploitation attempts began on Sept. 22 and likely continued into early October. During that window, the actor successfully compromised at least nine global entities across the technology, defense, healthcare, energy and education industries.

Following initial exploitation, a payload was uploaded to the victim network which installed a Godzilla webshell. This activity was consistent across all victims; however, we also observed a smaller subset of compromised organizations who subsequently received a modified version of a new backdoor called NGLite. The threat actors then used either the webshell or the NGLite payload to run commands and move laterally to other systems on the network, while they exfiltrated files of interest simply by downloading them from the web server. Once the actors pivoted to a domain controller, they installed a new credential-stealing tool that we track as KdcSponge.

Both Godzilla and NGLite were developed with Chinese instructions and are publicly available for download on GitHub. We believe threat actors deployed these tools in combination as a form of redundancy to maintain access to high-interest networks. Godzilla is a functionality-rich webshell that parses inbound HTTP POST requests, decrypts the data with a secret key, executes decrypted content to carry out additional functionality and returns the result via a HTTP response. This allows attackers to keep code likely to be flagged as malicious off the target system until they are ready to dynamically execute it.

NGLite is characterized by its author as an “anonymous cross-platform remote control program based on blockchain technology.” It leverages New Kind of Network (NKN) infrastructure for its command and control (C2) communications, which theoretically results in anonymity for its users. It’s important to note that NKN is a legitimate networking service that uses blockchain technology to support a decentralized network of peers. The use of NKN as a C2 channel is very uncommon. We have seen only 13 samples communicating with NKN altogether – nine NGLite samples and four related to a legitimate open-source utility called Surge that uses NKN for file sharing.

Finally, KdcSponge is a novel credential-stealing tool that is deployed against domain controllers to steal credentials. KdcSponge injects itself into the Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) process and will hook specific functions to gather usernames and passwords from accounts attempting to authenticate to the domain via Kerberos. The malicious code writes stolen credentials to a file but is reliant on other capabilities for exfiltration.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected against this campaign through the following:

- Cortex XDR local analysis blocks the NGLite backdoor.

- All known samples (Dropper, NGLite, KdcSponge) are classified as malware in WildFire.

- Cortex Xpanse can accurately identify Zoho ManageEngine ADSelfServicePlus, ManageEngine Desktop Central or ManageEngine ServiceDeskPlus Servers across customer networks.

Initial Access

Beginning on Sept. 17 and continuing through early October, we observed scanning against ManageEngine ADSelfService Plus servers. Through global telemetry, we believe that the actor targeted at least 370 Zoho ManageEngine servers in the United States alone. Given the scale, we assess that these scans were largely indiscriminate in nature as targets ranged from education to Department of Defense entities.

Upon obtaining scan results, the threat actor transitioned to exploitation attempts on Sept. 22. These attempts focused on CVE-2021-40539, which allows for REST API authentication bypass with resultant remote code execution in vulnerable devices. To achieve this result, the actors delivered uniquely crafted POST statements to the REST API LicenseMgr.

While we lack insight into the totality of organizations that were exploited during this campaign, we believe that, globally, at least nine entities across the technology, defense, healthcare, energy and education industries were compromised. Following successful exploitation, the actor uploaded a payload which deployed a Godzilla webshell, thereby enabling additional access to a victim network. The following leased IP addresses in the United States were observed interacting with compromised servers:

24.64.36[.]238

45.63.62[.]109

45.76.173[.]103

45.77.121[.]232

66.42.98[.]156

140.82.17[.]161

149.28.93[.]184

149.248.11[.]205

199.188.59[.]192

Following the deployment of the webshell, which appears consistent across all victims, we also identified the use of additional tools deployed in a subset of compromised networks. Specifically, the actors deployed a custom variant of an open-source backdoor called NGLite and a credential-harvesting tool we track as KdcSponge. The following sections provide detailed analysis of these tools.

Malware

At the time of exploitation, two different executables were saved to the compromised server: ME_ADManager.exe and ME_ADAudit.exe. The ME_ADManager.exe file acts as a dropper Trojan that not only saves a Godzilla webshell to the system, but also installs and runs the other executable saved to the system, specifically ME_ADAudit.exe. The ME_ADAudit.exe executable is based on NGLite, which the threat actors use as their payload to run commands on the system.

ME_ADManager.exe Dropper

After initial exploitation, the dropper is saved to the following path:

c:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\ADManager\ME_ADManager.exe

Analysis of this file revealed that the author of this payload did not remove debug symbols when building the sample. Thus, the following debug path exists within the sample and suggests the username pwn was used to create this payload:

c:\Users\pwn\documents\visual studio 2015\Projects\payloaddll\Release\cmd.pdb

Upon execution, the sample starts off by creating the following generic mutex found in many code examples freely available on the internet, which is meant to avoid running more than one instance of the dropper:

cplusplus_me

The dropper then attempts to write a hardcoded Godzilla webshell, which we will provide a detailed analysis of later in this report, to the following locations:

../webapps/adssp/help/admin-guide/reports.jsp

c:/ManageEngine/ADSelfService Plus/webapps/adssp/help/admin-guide/reports.jsp

../webapps/adssp/selfservice/assets/fonts/lato/lato-regular.jsp

c:/ManageEngine/ADSelfService Plus/webapps/adssp/selfservice/assets/fonts/lato/lato-regular.jsp

The dropper then creates the folder %APPDATA%\ADManager and copies itself to %APPDATA%\ADManager\ME_ADManager.exe before creating the following registry keys to persistently run after reboot:

Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\ME_ADManager.exe : %APPDATA%\ADManager\ME_ADManager.exe

Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\ME_ADAudit.exe : %SYSTEM32%\ME_ADAudit.exe

The dropper then copies ADAudit.exe from the current directory to the following path and runs the file with WinExec:

%SYSTEM32%\ME_ADAudit.exe

The dropper does not write the ME_ADAudit.exe file to disk, meaning the threat actor must upload this file to the server prior to the execution of the dropper, likely as part of the initial exploitation of the CVE-2021-40539 vulnerability. During our analysis of multiple incidents, we found that the ME_ADAudit.exe sample maintained a consistent SHA256 hash of 805b92787ca7833eef5e61e2df1310e4b6544955e812e60b5f834f904623fd9f, therefore suggesting that the actor deployed the same customized version of the NGLite backdoor against multiple targets.

Godzilla Webshell

As mentioned previously, the initial dropper contains a Java Server Page (JSP) webshell hardcoded within it. Upon analysis of the webshell, it was determined to be the Chinese-language Godzilla webshell V3.00+. The Godzilla webshell was developed by user BeichenDream, who stated they created this webshell because the ones available at the time would frequently be detected by security products during red team engagements. As such, the author advertises it will avoid detection by leveraging AES encryption for its network traffic and that it maintains a very low static detection rate across security vendor products.

It’s no surprise that the Godzilla webshell has been adopted by regional threat groups during their intrusions, as it offers more functionality and network evasion than other webshells used by the same groups, such as ChinaChopper.

The JSP webshell itself is fairly straightforward in terms of functionality and maintains a lightweight footprint. Its primary function is to parse an HTTP POST, decrypt the content with the secret key and then execute the payload. This allows attackers to keep code likely to be flagged as malicious off the target system until they are ready to dynamically execute it.

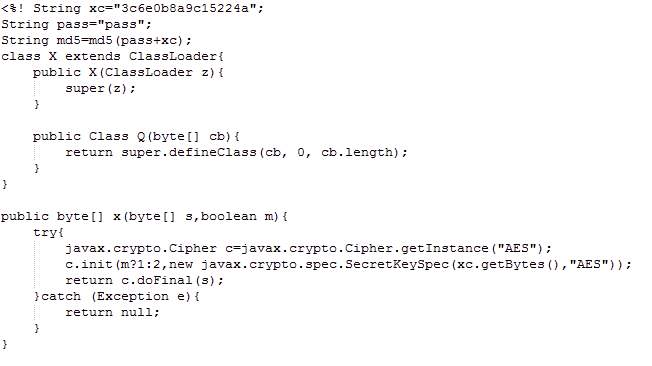

The below image shows the initial part of the default JSP webshell as well as the decrypt function.

Of note are the variables xc and pass in the first and second lines of the code shown in Figure 2. These are the main components that change each time an operator generates a new webshell, and the variables represent the secret key used for AES decryption within that webshell.

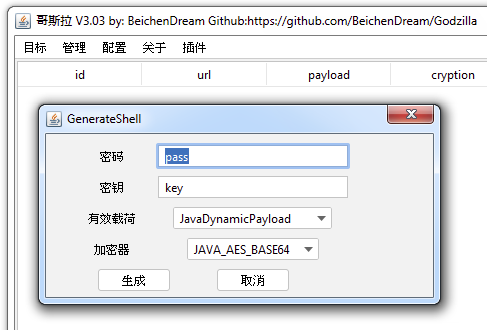

When you generate the webshell manually, you specify a plaintext pass and key. By default, these are pass and key.

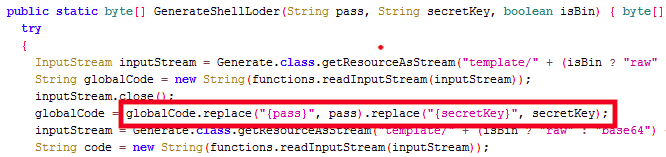

To figure out how these are presented in the webshell itself, we can take a look at the Godzilla JAR file.

Below, you can see the code substitutes the strings in one of the embedded webshell templates under the /shells/cryptions/JavaAES/GenerateShellLoder function.

Thus we know the xc variable in the webshell will be the AES secret key, as indicated in the template.

String xc=”{secretKey}”; String pass=”{pass}”; String md5=md5(pass+xc);

We observed that the xc value appears to be a hash, and under the /core/shell/ShellEntity.class file, we can see the code takes the first 16 characters of the MD5 hash for a plaintext secret key.

public String getSecretKeyX()

{

return functions.md5(getSecretKey()).substring(0, 16);

}

With that, we know then that the xc value of 3c6e0b8a9c15224a is the first 16 characters of the MD5 hash for the word key.

Given this, the xc and pass variables are the two primary fields that can be used for tracking and attempting to map activity across incidents. For the purpose of this blog, we generated a Godzilla webshell with the default options for analysis; however, the only differences between the default one and the ones observed in attacks are different xc and pass values.

One important characteristic of this webshell is that the author touts the lack of static detection and has tried to make this file not stand out through avoiding keywords or common structures that might be recognized by security product signatures. One particularly interesting static evasion technique is the use of a Java ternary conditional operator to indicate decryption.

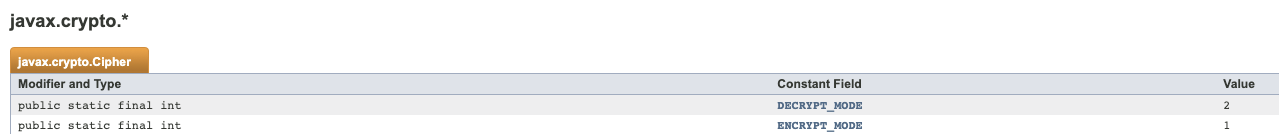

The conditional here is m?1:2 – m is a boolean value passed to this function, as shown previously in Figure 2. If m is True, then the first expression constant (1) is used. Otherwise, the second (2) is passed. Referring to the Java documentation, 1 is ENCRYPT_MODE, whereas 2 is DECRYPT_MODE.

When the webshell executes this function x, it does not set the value of m, thus forcing m to False and setting it to decrypt.

response.getWriter().write(base64Encode(x(base64Decode(f.toString()), true)));

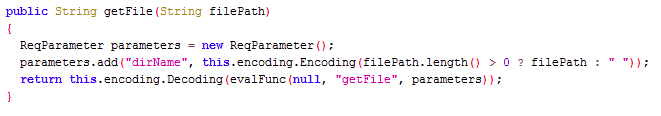

To understand the capabilities of Godzilla then, we can take a look in /shells/payloads/java/JavaShell.class. This class file contains all of the functions provided to the operator. Below is an example of the getFile function.

Payload functions:

getFile

downloadFile

getBasicsInfo

uploadFile

copyFile

deleteFile

newFile

newDir

currentDir

currentUserName

bigFileUpload

bigFileDownload

getFileSize

execCommand

getOsInfo

moveFile

getPayload

fileRemoteDown

setFileAttr

As evidenced by the names of the functions, the Godzilla webshell offers numerous payloads for navigating remote systems, transferring data to and from, remote command execution and enumeration.

These payloads will be encrypted with the secret key previously described, and the operating software will send an HTTP POST to the compromised system containing the data.

Additionally, if we examine the core/ui/component/dialog/ShellSetting.class file (shown below), the initAddShellValue() function contains the default configuration settings for remote network access. Therefore, elements such as static HTTP headers and User-Agent strings can be identified in order to aid forensic efforts searching web access logs for potential compromise.

private void initAddShellValue() {

this.shellContext = new ShellEntity();

this.urlTextField.setText(“http://127.0.0.1/shell.jsp”);

this.passwordTextField.setText(“pass”);

this.secretKeyTextField.setText(“key”);

this.proxyHostTextField.setText(“127.0.0.1”);

this.proxyPortTextField.setText(“8888”);

this.connTimeOutTextField.setText(“60000”);

this.readTimeOutTextField.setText(“60000”);

this.remarkTextField.setText(“??”);

this.headersTextArea.setText(“User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT

10.0; Win64; x64; rv:84.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/84.0\nAccept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8\nAccept-Language:

zh-CN,zh;q=0.8,zh-TW;q=0.7,zh-HK;q=0.5,en-US;q=0.3,en;q=0.2\n”);

this.leftTextArea.setText(“”);

this.rightTextArea.setText(“”);

}

To illustrate, below is a snippet of the web server access logs that show the initial exploit using the Curl application and sending the custom URL payload to trigger the CVE-2021-40539 vulnerability. It then shows the subsequent access of the Godzilla webshell, which has been placed into the hardcoded paths by the initial dropper. By reviewing the User-Agent, we can determine that the time from exploit to initial webshell access took just over four minutes for the threat actor.

– /./RestAPI/LicenseMgr “-” X.X.X.X Y.Y.Y.Y POST [00:00:00] – – 200 “curl/7.68.0”

– /help/admin-guide/reports.jsp “-” X.X.X.X Y.Y.Y.Y POST [+00:04:07] – – 200 “Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64; rv:84.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/84.0”

Custom NGLite

NGLite is an open-source backdoor written in the Go language (specifically Go version 1.13). It is available for download from a public GitHub repository. NGLite is a backdoor Trojan that is only capable of running commands received through its C2 channel. While the capabilities are standard for a backdoor, NGLite uses a novel C2 channel that leverages a decentralized network based on the legitimate NKN to communicate between the backdoor and the actors.

The NKN touts that their decentralized network uses a public blockchain and can support communication between millions of peers, each of which are identified by a unique NKN address instead of the typical network identifiers, such as IP addresses. Therefore, the immediate IP address that the NGLite tool communicates with in its C2 channel is just a peer in the decentralized network and is unlikely to represent the threat actor’s network location. This design makes detection and prevention of the NGLite C2 communication channel difficult.

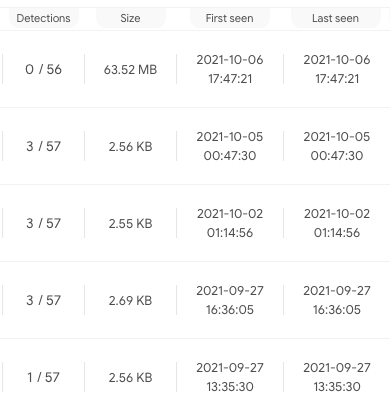

Fortunately, the use of NKN as a C2 channel is very uncommon. We have seen only 13 samples communicating with NKN altogether – nine NGLite samples and four related to an open-source utility called Surge that uses NKN for file sharing. Eight of the nine known NGLite samples were scanned by VirusTotal. Four were undetected, three were detected by one antivirus and the remaining sample was detected by five. This low detection rate suggests that NGLite had very little antivirus coverage during this attack campaign.

As mentioned in the previous section, the dropper creates registry keys and executes a custom variant of the NGLite backdoor (SHA256: 805b92787ca7833eef5e61e2df1310e4b6544955e812e60b5f834f904623fd9f) saved at the following path:

C:\Windows\system32\ME_ADAudit.exe

The data structures within the Go-based backdoor contain the following path, which is used to store the main source code for this custom variant of NGLite on the developers’ system:

/mnt/hgfs/CrossC2-2.2/src/ng.com/lprey/main.go

Based on this path, one might surmise that the actor used CrossC2 to build a cross platform Cobalt Strike C2 payload; however, we have no reason to believe that this payload is actually based on CrossC2, as the payload is a customized version of the publicly available NGLite backdoor.

It is possible that the threat actors included the CrossC2 string in the path as a misdirection, hoping to confuse threat analysts into thinking they are delivering a Cobalt Strike payload. We have seen the following NGLite samples using this same source code path dating back to Aug. 11, which suggests that this threat actor has been using this tool for several months:

3da8d1bfb8192f43cf5d9247035aa4445381d2d26bed981662e3db34824c71fd

5b8c307c424e777972c0fa1322844d4d04e9eb200fe9532644888c4b6386d755

3f868ac52916ebb6f6186ac20b20903f63bc8e9c460e2418f2b032a207d8f21d

The custom NGLite sample used in this campaign checks the command line arguments for g or group value. If this switch is not present, the payload will use the default string 7aa7ad1bfa9da581a7a04489896279517eef9357b81e406e3aee1a66101fe824 in what NGLite refers to as its seed identifier.

The payload will create what it refers to as a prey id, which is generated by concatenating the MAC address of the system network interface card (NIC) and IPv4 address, with a hyphen (-) separating the two. This prey identifier will be used in the C2 communications.

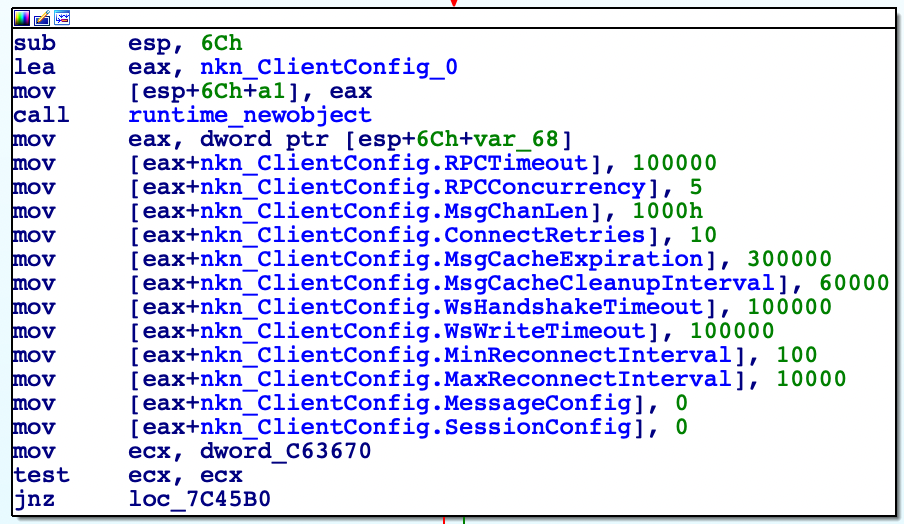

The NGLite payload will use the NKN decentralized network for C2 communications. See the NKN client configuration in the sample below:

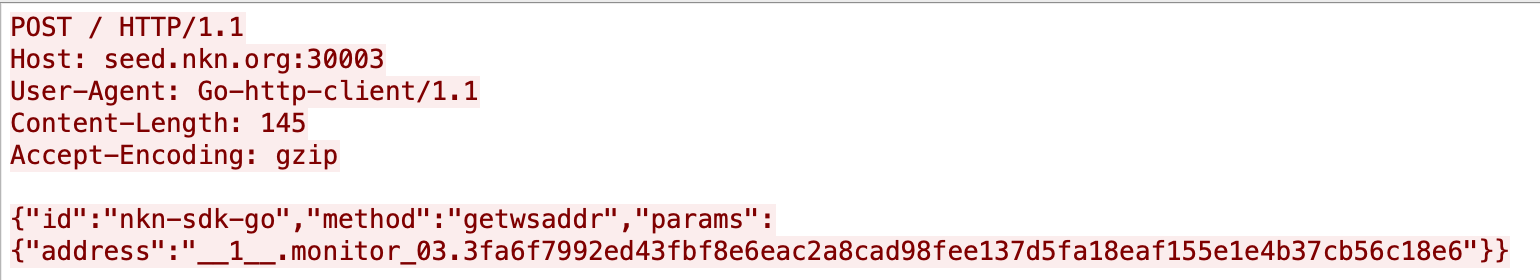

The sample first starts by reaching out to seed.nkn[.]org over TCP/30003, specifically with an HTTP POST request that is structured as follows:

![The sample first starts by reaching out to seed.nkn[.]org over TCP/30003, specifically with an HTTP POST request that is structured as shown.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/word-image-7.png)

It also will send HTTP POST requests with monitor_03 as the prey id, as seen in the following:

The seed.nkn[.]org server responds to this request with the [prey id (MAC-IPv4)] within the JSON structured as follows:

{“id”:”nkn-sdk-go”,”jsonrpc”:”2.0″,”result”:{“addr”:”66.115.12.89:30002″,”id”:”223b4f7f4588af02badaa6a83e402b33dea0ba8908e4cd6008f84c2b98a6a7de”,”pubkey”:”38ce48a2a3cffded7c2031514acaef29851ee39303795e4b3e7fce5a6619e6be”,”rpcAddr”:”66.115.12.89:30003″}}

This suggests the payload will communicate with the peer at 66.115.12.89 over TCP/30003. The seed.nkn[.]org server then responds to the monitor_03 request with the following, which suggests the payload will communicate with 54.204.73.156 over TCP/30003:

{“id”:”nkn-sdk-go”,”jsonrpc”:”2.0″,”result”:{“addr”:”54.204.73.156:30002″,”id”:”517cb8112456e5d378b0de076e85e80afee3c483d18c30187730d15f18392ef9″,”pubkey”:”99bb5d3b9b609a31c75fdeede38563b997136f30cb06933c9b43ab3f719369aa”,”rpcAddr”:”54.204.73.156:30003″}}

After obtaining the response from seed.nkn[.]org, the payload will issue an HTTP GET request to the IP address and TCP port provided in the addr field within the JSON. These HTTP requests will appear as follows, but keep in mind that these systems are not actor-controlled; rather, they are just the first peer in a chain of peers that will eventually return the actor’s content:

![After obtaining the response from seed.nkn[.]org, the payload will issue an HTTP GET request to the IP address and TCP port provided in the addr field within the JSON. These HTTP requests will appear as shown, but keep in mind that these systems are not actor-controlled; rather, they are just the first peer in a chain of peers that will eventually return the actor’s content.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/word-image-9.png)

Eventually, the network communications between the custom NGLite client and server are encrypted using AES with the following key:

WHATswrongwithUu

The custom NGLite sample will start by sending the C2 an initial beacon that contains the result of the whoami command with the string #windows concatenated, as seen in the following:

[username]#windows

After sending the initial beacon, the NGLite sample will run a sub-function called Preylistener that creates a server that listens for inbound requests. The sample will also listen for inbound communications and will attempt to decrypt them using a default AES key of 1234567890987654. It will run the decrypted contents as a command via the Go method os/exec.Command. The results are then encrypted using the same AES key and sent back to the requester.

Post-exploitation Activity

Upon compromising a network, the threat actor moved quickly from their initial foothold to gain access to other systems on the target networks by running commands via their NGLite payload and the Godzilla webshell. After gaining access to the initial server, the actors focused their efforts on gathering and exfiltrating sensitive information from local domain controllers, such as the Active Directory database file (ntds.dit) and the SYSTEM hive from the registry. Shortly after, we observed the threat actors installing the KdcSponge credential stealer, which we will discuss in detail next. Ultimately, the actor was interested in stealing credentials, maintaining access and gathering sensitive files from victim networks for exfiltration.

Credential Harvesting and KdcSponge

During analysis, Unit 42 found logs that suggest the threat actors used PwDump and the built-in comsvcs.dll to create a mini dump of the lsass.exe process for credential theft; however, when the actor wished to steal credentials from a domain controller, they installed their custom tool that we track as KdcSponge.

The purpose of KdcSponge is to hook API functions from within the LSASS process to steal credentials from inbound attempts to authenticate via the Kerberos service (“KDC Service”). KdcSponge will capture the domain name, username and password to a file on the system that the threat actor would then exfiltrate manually through existing access to the server.

We know of two KdcSponge samples, both of which were named user64.dll. They had the following SHA256 hashes:

3c90df0e02cc9b1cf1a86f9d7e6f777366c5748bd3cf4070b49460b48b4d4090

b4162f039172dcb85ca4b85c99dd77beb70743ffd2e6f9e0ba78531945577665

To launch the KdcSponge credential stealer, the threat actor will run the following command to load and execute the malicious module:

regsvr32 /s user64.dll

Upon first execution, the regsvr32 application runs the DllRegisterServer function exported by user64.dll. The DllRegisterServer function resolves the SetSfcFileException function within sfc_os.dll and attempts to disable Windows File Protection (WFP) on the c:\windows\system32\kdcsvc.dll file. It then attempts to inject itself into the running lsass.exe process by:

1. Opening the lsass.exe process using OpenProcess.

2. Allocating memory in the remote process using VirtualAllocEx.

3. Writing the string user64.dll to the allocated memory using WriteProcessMemory.

4. Calling LoadLibraryA within the lsass.exe process with user64.dll as the argument, using RtlCreateUserThread.

Now that user64.dll is running within the lsass.exe process, it will start by creating the following registry key to establish persistence through system reboots:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce\KDC Service : regsvr32 /s user64.dll

From there, the sample will check to make sure the system is running a Kerberos service by attempting to obtain a handle to one of the following modules:

kdcsvc.dll

kdccli.dll

Kdcsvs.dll

KdcSponge tries to locate three undocumented API functions – specifically KdcVerifyEncryptedTimeStamp, KerbHashPasswordEx3 and KerbFreeKey – using the following three methods:

- Identifies the version of Kerberos module and uses hardcoded offsets to API functions to hook.

- Reaches out to Microsoft’s symbol server to find the offset to API functions within Kerberos module and confirms the correct functions by comparing to hardcoded byte sequences.

- Searches the Kerberos module for hardcoded byte sequences.

The primary method in which KdcSponge locates the API functions to hook is based on determining the version of the Kerberos module based on the TimeDateStamp value within the IMAGE_FILE_HEADER section of the portable executable (PE) file. Once the version of the Kerberos module is determined, KdcSponge has hardcoded offsets that it will use to hook the appropriate functions within that version of the module. KdcSponge looks for the following TimeDateStamp values:

2005-12-14 01:24:41

2049-10-09 00:46:34

2021-04-08 07:30:26

2021-03-04 04:59:27

2020-03-13 03:20:15

2020-02-19 07:55:57

2019-12-19 04:15:06

2019-07-09 03:15:04

2019-05-31 06:02:30

2018-10-10 07:46:08

2018-02-12 21:47:29

2017-03-04 06:27:32

2016-10-15 03:52:20

2020-11-26 03:04:23

2020-06-05 16:15:22

2017-10-14 07:22:03

2017-03-30 19:53:59

2013-09-04 05:49:27

2012-07-26 00:01:13

If KdcSponge was unable to determine the version of the Kerberos module and the domain controller is running Windows Server 2016 or Server 2019 (major version 10), the payload will reach out to Microsoft’s symbol server (msdl.microsoft.com) in an attempt to find the location of several undocumented API functions. The sample will issue an HTTPS GET request to a URL structured as follows, with the GUID portion of the URL being the GUID value from the RSDS structure in the IMAGE_DEBUG_TYPE_CODEVIEW section of the PE:

/download/symbols/[library name].pdb/[GUID]/[library name].pdb

The sample will save the results to a file in the following location, again with the GUID for the filename being the GUID value from the RSDS structure in the IMAGE_DEBUG_TYPE_CODEVIEW section:

ALLUSERPROFILE\Microsoft\Windows\Caches\[GUID].db:

As mentioned above, we believe the reason the code reaches out to the symbol server is to find the locations of three undocumented Kerberos-related functions: KdcVerifyEncryptedTimeStamp, KerbHashPasswordEx3 and KerbFreeKey. The sample is primarily looking for these functions in the following libraries:

kdcsvc.KdcVerifyEncryptedTimeStamp

kdcsvc.KerbHashPasswordEx3

kdcpw.KerbHashPasswordEx3

kdcsvc.KerbFreeKey

kdcpw.KerbFreeKey

If these functions are found, the sample searches for specific byte sequences, as seen in Table 1, to confirm the functions are correct and to validate they have not been modified.

| Function | Hex bytes |

| kdcsvc.KdcVerifyEncryptedTimeStamp | 48 89 5c 24 20 55 56 57 41 54 41 55 41 56 41 57 48 8d 6c 24 f0 48 81 ec 10 01 00 00 48 8b 05 a5 |

| kdcsvc.KerbHashPasswordEx3 | 48 89 5c 24 08 48 89 74 24 10 48 89 7c 24 18 55 41 56 41 57 48 8b ec 48 83 ec 50 48 8b da 48 8b |

| kdcpw.KerbHashPasswordEx3 | 48 89 5c 24 08 48 89 74 24 10 48 89 7c 24 18 55 41 56 41 57 48 8b ec 48 83 ec 50 48 8b da 48 8b |

| kdcpw.KerbFreeKey | 48 89 5c 24 08 57 48 83 ec 20 48 8b d9 33 c0 8b 49 10 48 8b 7b 18 f3 aa 48 8b 4b 18 ff 15 72 19 |

| kdcsvc.KerbFreeKey | 48 89 5c 24 08 57 48 83 ec 20 48 8b 79 18 48 8b d9 48 85 ff 0f 85 00 c5 01 00 33 c0 48 89 03 48 |

Table 1. Undocumented functions and byte sequences used by KdcSponge to confirm the correct functions for Windows major version 10.

If the domain controller is running Windows Server 2008 or Server 2012 (major version 6), KdcSponge does not reach out to the symbol server and instead will search the entire kdcsvc.dll module for the byte sequences listed in Table 2 to find the API functions.

| Function | Hex bytes |

| kdcsvc.KdcVerifyEncryptedTimeStamp | 48 89 5C 24 20 55 56 57 41 54 41 55 41 56 41 57 48 8D 6C 24 F9 48 81 EC C0 00 00 00 48 8B |

| kdcsvc.KerbHashPasswordEx3 | 48 89 5C 24 08 48 89 74 24 10 48 89 7C 24 18 55 41 56 41 57 48 8B EC 48 83 EC 40 48 8B F1 |

| kdcsvc.KerbFreeKey | 40 53 48 83 EC 20 48 8B D9 48 8B 49 10 48 85 C9 0F 85 B4 B9 01 00 33 C0 48 89 03 48 89 43 |

Table 2. Undocumented functions and byte sequences used by KdcSponge to locate the sought after functions.

Once the KdcVerifyEncryptedTimeStamp, KerbHashPasswordEx3 and KerbFreeKey functions are found, the sample will attempt to hook these functions to monitor all calls to them with the intention to steal credentials. When a request to authenticate to the domain controller comes in, these functions in the Kerberos service (KDC service) are called, and the sample will capture the inbound credentials. The credentials are then written to disk at the following location:

%ALLUSERPROFILE%\Microsoft\Windows\Caches\system.dat

The stolen credentials are encrypted with a single-byte XOR algorithm using 0x55 as the key and written to the system.dat file one per line in the following structure:

[<timestamp>]<domain><username> <cleartext password>

Attribution

While attribution is still ongoing and we have been unable to validate the actor behind the campaign, we did observe some correlations between the tactics and tooling used in the cases we analyzed and Threat Group 3390 (TG-3390, Emissary Panda, APT27).

Specifically, as documented by SecureWorks in an article on a previous TG-3390 operation, we can see that TG-3390 similarly used web exploitation and another popular Chinese webshell called ChinaChopper for their initial footholds before leveraging legitimate stolen credentials for lateral movement and attacks on a domain controller. While the webshells and exploits differ, once the actors achieved access into the environment, we noted an overlap in some of their exfiltration tooling.

SecureWorks stated the actors were using WinRar masquerading as a different application to split data into RAR archives within the Recycler directory. They provided the following snippet from a Batch file deployed to do this work:

@echo off

c:\windows\temp\svchost.exe a -k -r -s -m5 -v1024000 -padmin-windows2014 “e:\recycler\REDACTED.rar” “e:\ProgramData\REDACTED\”

Exit

From our analysis of recent attacks on ManageEngine ADSelfService Plus, we observed the same technique – with the same order and placement of the parameters passed to a renamed WinRar application.

@echo off

dir %~dp0>>%~dp0\log.txt

%~dp0\vmtools.exe a -k -r -s -m5 -v4096000 -pREDACTED “e:\$RECYCLE.BIN\REDACTED.rar” “E:\Programs\REDACTED\REDACTED”

Once the files had been staged, in both cases they were then made accessible on externally facing web servers. The threat actors would then download them through direct HTTP GET requests.

Conclusion

In September 2021, Unit 42 observed an attack campaign in which the actors gained initial access to targeted organizations by exploiting a recently patched vulnerability in Zoho’s ManageEngine product, ADSelfService Plus, tracked in CVE-2021-40539. At least nine entities across the technology, defense, healthcare, energy and education industries were compromised in this attack campaign.

After exploitation, the threat actor quickly moved laterally through the network and deployed several tools to run commands in order to carry out their post-exploitation activities. The actor heavily relies on the Godzilla webshell, uploading several variations of the open-source webshell to the compromised server over the course of the operation. Several other tools have novel characteristics or have not been publicly discussed as being used in previous attacks, specifically the NGLite backdoor and the KdcSponge stealer. For instance, the NGLite backdoor uses a novel C2 channel involving the decentralized network known as the NKN, while the KdcSponge stealer hooks undocumented functions to harvest credentials from inbound Kerberos authentication attempts to the domain controller.

Unit 42 believes that the actor’s primary goal involved gaining persistent access to the network and the gathering and exfiltration of sensitive documents from the compromised organization. The threat actor gathered sensitive files to a staging directory and created password-protected multi-volume RAR archives in the Recycler folder. The actor exfiltrated the files by directly downloading the individual RAR archives from externally facing web servers.

The following coverages across the Palo Alto Networks platform pertain to this incident:

- Threat Prevention signature ZOHO corp ManageEngine Improper Authentication Vulnerability was released on Sept. 20 as threat ID 91676.

- NGLite backdoor is blocked by Cortex XDR’s local analysis.

- All known samples (Dropper, NGLite, KdcSponge) are classified as malware in WildFire.

- Cortex Xpanse can accurately identify Zoho ManageEngine ADSelfServicePlus, ManageEngine Desktop Central, or ManageEngine ServiceDeskPlus Servers across customer networks.

If you think you may have been impacted, please email unit42-investigations@paloaltonetworks.com or call (866) 486-4842 – (866) 4-UNIT42 – for U.S. toll free, (31-20) 299-3130 in EMEA or (65) 6983-8730 in JAPAC. The Unit 42 Incident Response team is available 24/7/365.

Special thanks to Unit 42 Consulting Services and the NSA Cybersecurity Collaboration Center for their partnership, collaboration and insights offered in support of this research.

Palo Alto Networks has shared these findings, including file samples and indicators of compromise, with our fellow Cyber Threat Alliance members. CTA members use this intelligence to rapidly deploy protections to their customers and to systematically disrupt malicious cyber actors. Learn more about the Cyber Threat Alliance.

Indicators of Compromise

Dropper SHA256

b2a29d99a1657140f4e254221d8666a736160ce960d06557778318e0d1b7423b

5fcc9f3b514b853e8e9077ed4940538aba7b3044edbba28ca92ed37199292058

NGLite SHA256

805b92787ca7833eef5e61e2df1310e4b6544955e812e60b5f834f904623fd9f

3da8d1bfb8192f43cf5d9247035aa4445381d2d26bed981662e3db34824c71fd

5b8c307c424e777972c0fa1322844d4d04e9eb200fe9532644888c4b6386d755

3f868ac52916ebb6f6186ac20b20903f63bc8e9c460e2418f2b032a207d8f21d

Godzilla Webshell SHA256

a44a5e8e65266611d5845d88b43c9e4a9d84fe074fd18f48b50fb837fa6e429d

ce310ab611895db1767877bd1f635ee3c4350d6e17ea28f8d100313f62b87382

75574959bbdad4b4ac7b16906cd8f1fd855d2a7df8e63905ab18540e2d6f1600

5475aec3b9837b514367c89d8362a9d524bfa02e75b85b401025588839a40bcb

KdcSponge SHA256

3c90df0e02cc9b1cf1a86f9d7e6f777366c5748bd3cf4070b49460b48b4d4090

b4162f039172dcb85ca4b85c99dd77beb70743ffd2e6f9e0ba78531945577665

Threat Actor IP Addresses

24.64.36[.]238

45.63.62[.]109

45.76.173[.]103

45.77.121[.]232

66.42.98[.]156

140.82.17[.]161

149.28.93[.]184

149.248.11[.]205

199.188.59[.]192

Registry Keys

Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\ME_ADManager.exe

Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\ME_ADAudit.exe

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\RunOnce\KDC Service

To read the original article:

https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/manageengine-godzilla-nglite-kdcsponge/